The Forgotten 4-weight

Everyone is always looking for the one easy answer to a question and the one simple solution to a problem. In fly fishing, maybe it’s the dry fly that won’t sink, the nymph that won’t hang the bottom, the wading boot that won’t slip or the perfect size mountain fly rod. Well, I can tell you if you’re still hoping to find any of those things, you will be sorely disappointed. But with the latter, the perfect size mountain fly rod, I believe you can come close!

A few years ago, I was guiding a couple of guys on what I would classify as a mid-size stream in the Smoky Mountains. They were both fishing 12’ tenkara rods and absolutely clobbering fish. They wanted to fish at the same time, so I had them spread out in different sections of the stream, and I repeatedly walked the trail back and forth between them to help and advise as needed.

During my travels up and down the trail, I ran into two other fishermen on three different occasions. They were friendly and chatted with me about the fishing each time. As usual in those situations, I was pleasant but tried to be brief. By the way, if you ever engage a working guide on the stream or trail and he or she seems short with you, don’t take it personally. They’re working.

But in my brief interactions with them, they were quick to tell me that they were not catching fish, and were asking for advice, mainly regarding fly patterns. The third time I saw them, they told me that they still weren’t catching fish but had figured out that the problem was their rods were too long. Each of them had a 7 ½’ rod. I didn’t have the heart to tell them that my clients were catching fish left and right with 12’ rods, but I did mention the benefits of longer rods and offered a little advice on how to fish the stream.

So, obviously you need a 12’ tenkara rod to catch a lot of fish in the Smokies, right? Wrong. I’ve seen plenty of fish caught on 7’ fly rods, too! Many anglers fall into the trap of blaming or crediting all of their success or failure on the gear, whether rods or flies. All of these things are just tools. And in the hands of someone who knows how to use them, all of these tools can be effective. A good carpenter will build a fine deck whether he uses a handsaw or a power saw. And a bad carpenter will build a crappy deck regardless of the tool he uses.

Of course, when it comes to choosing the right tool for the job, it often comes down to the task at hand. But it just as often comes down to the style, preference and philosophy of the person using the tool. It’s why I often give such cryptic replies to people who ask me what rod they should use in a specific location.

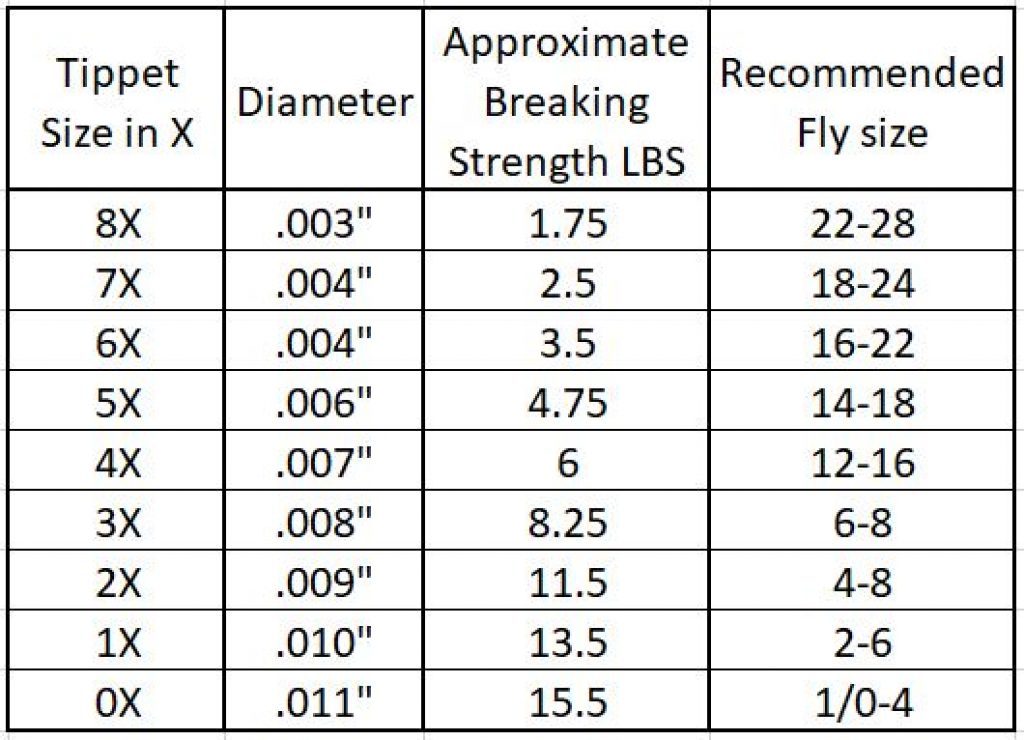

When it comes to mountain rods, or really, just trout rods in general, I immediately eliminate anything bigger than a 6-weight. Yes, you can catch a trout on an 8-weight, but unless you’re big river fishing with oversized streamers for huge trout, it just doesn’t make much sense. 3, 4 and 5-weight lines are really your bread and butter trout weights, particularly in the mountains. They’re heavy enough to cast most anything you’d need to cast, and still light enough to achieve delicate presentations and offer less drag on the water. 1 and 2-weight rods fall more into the specialty category. They are a lot of fun but a little too light to qualify as a legitimate all-purpose rod.

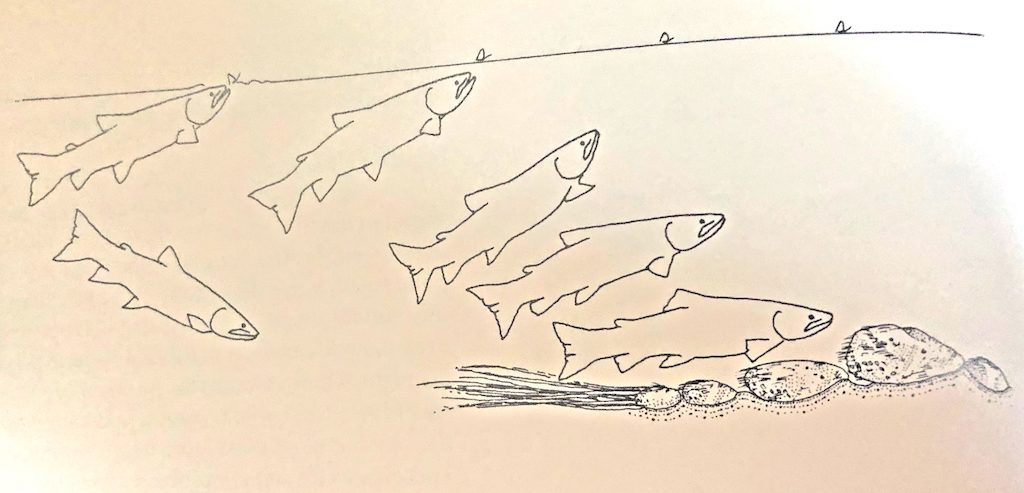

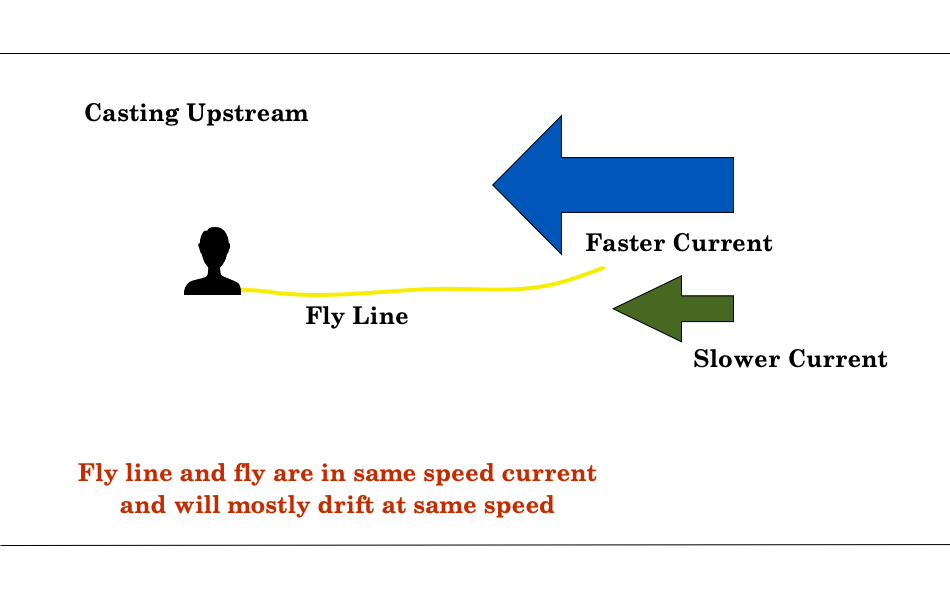

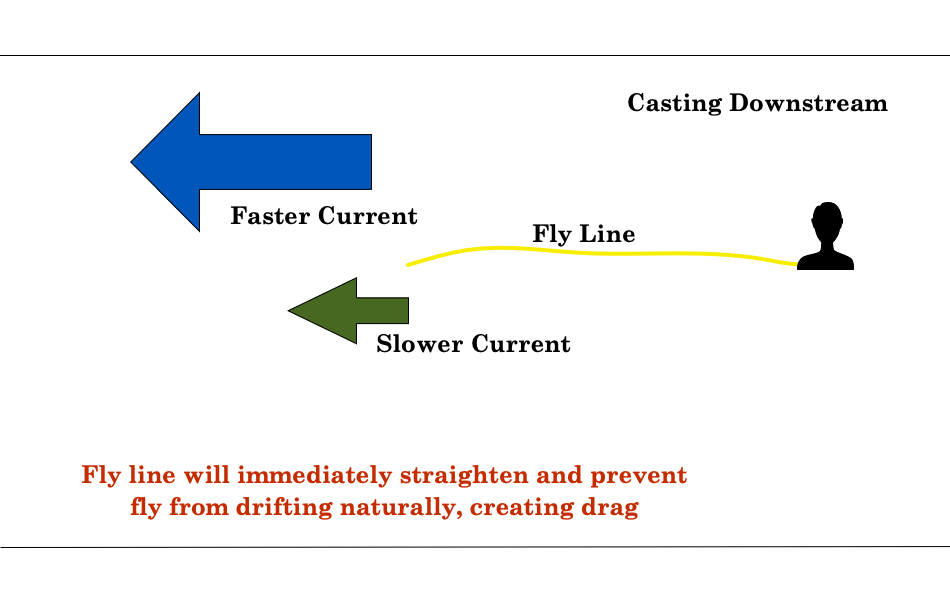

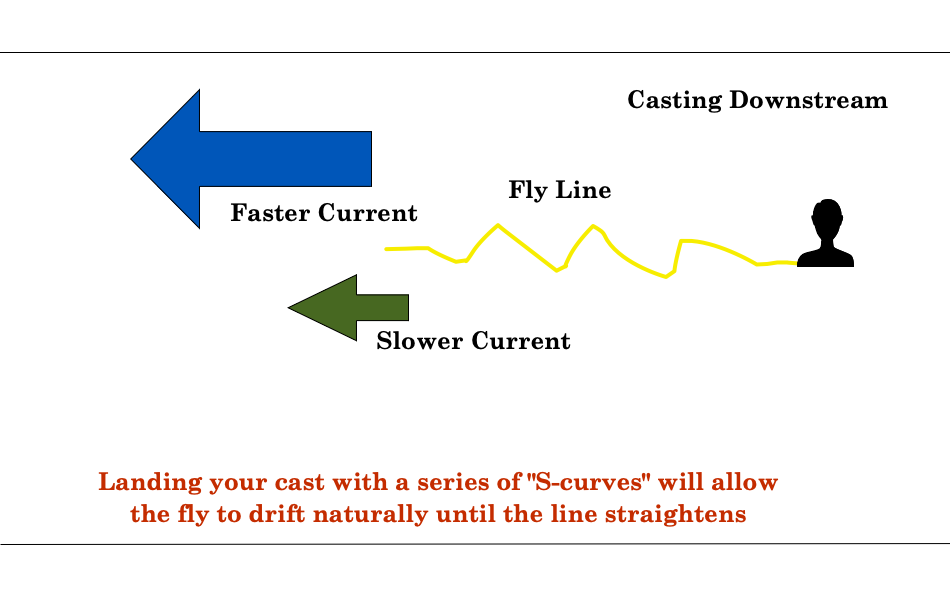

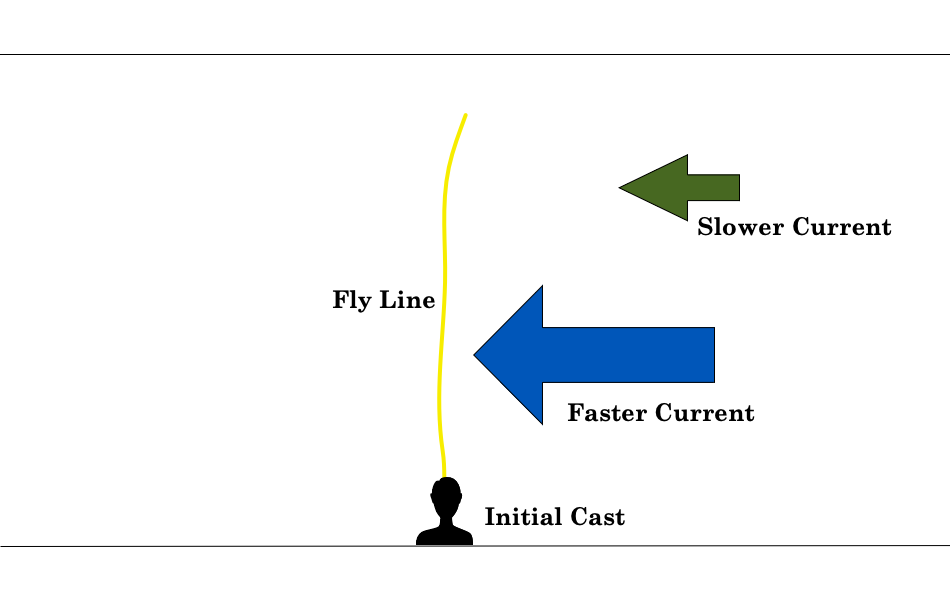

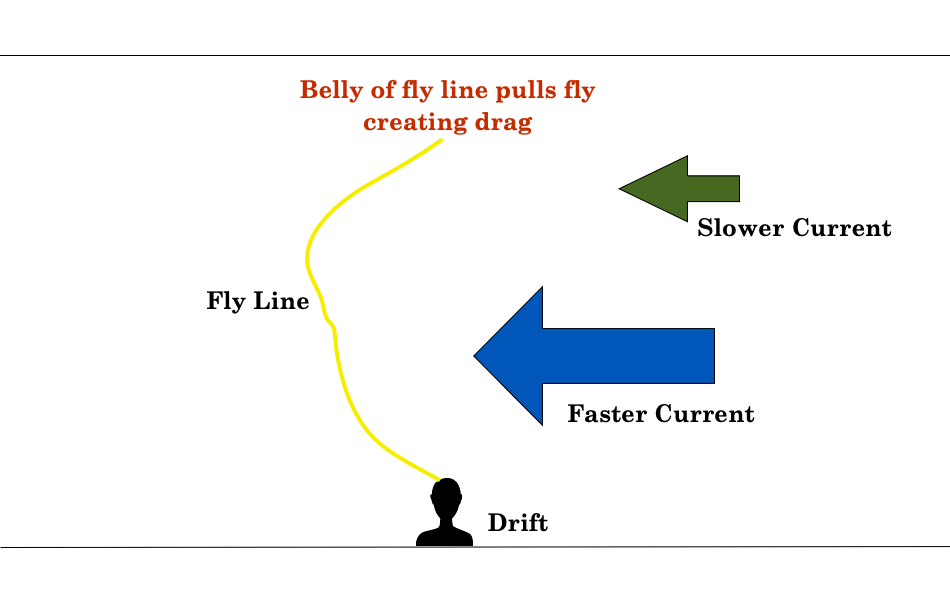

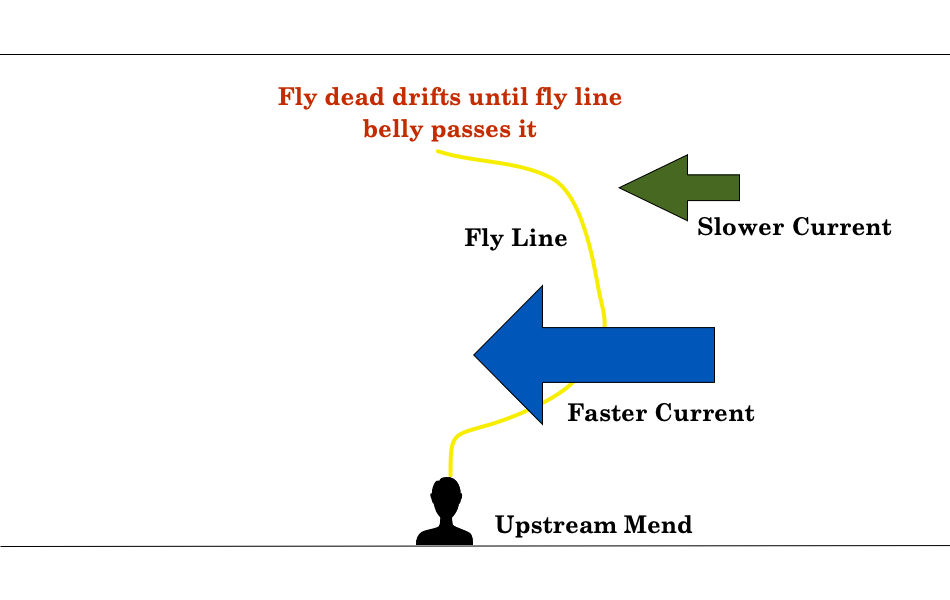

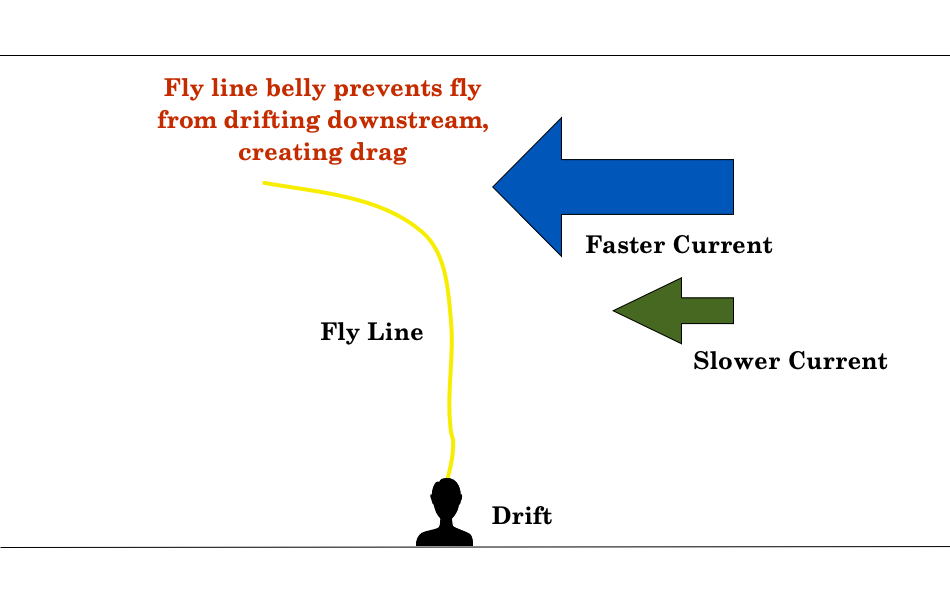

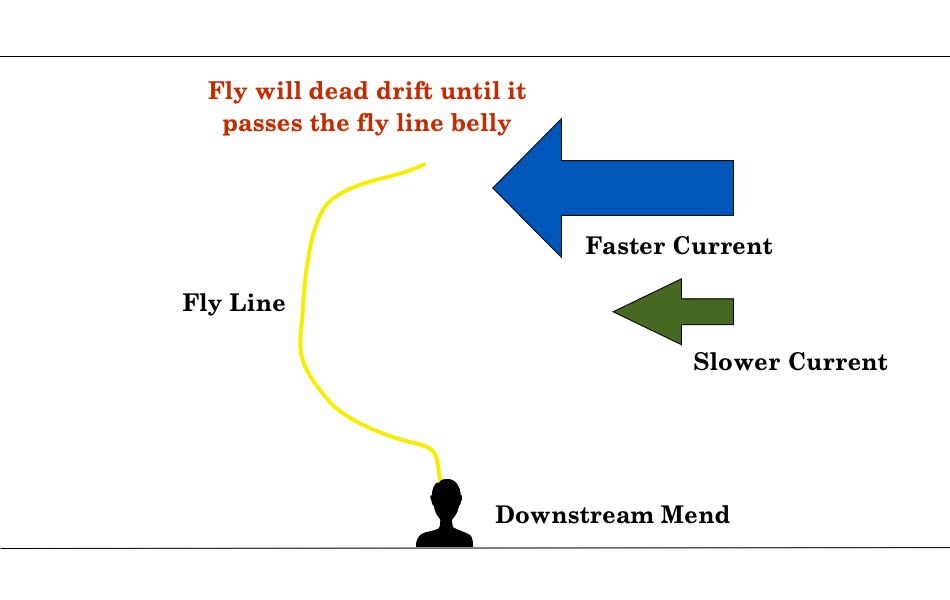

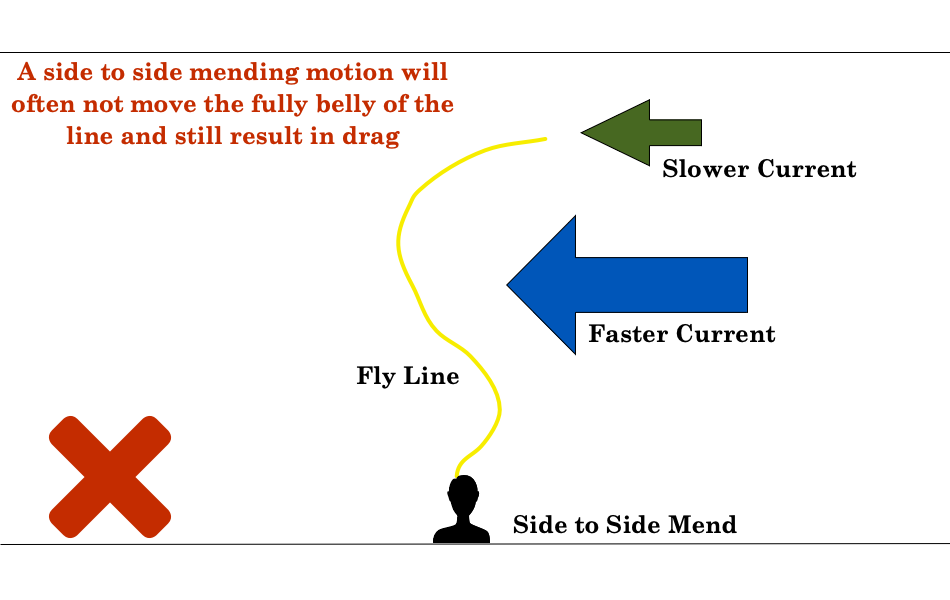

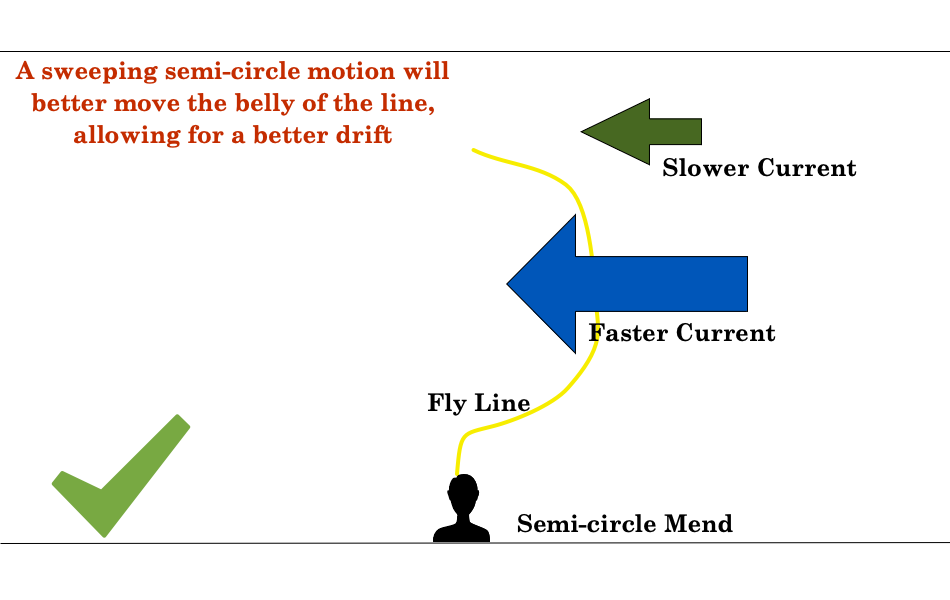

It’s similar when we talk about rod length. It used to be that everybody thought you needed a really short rod, like a 6 or 7-footer, to fish in the tighter streams found in the mountains. I think they envisioned making these really long casts and thought the shorter rod would help with that. However, for most folks who know what they’re doing on a mountain stream, the casts are very short, and a longer rod gives you more reach to keep the line off varying currents. Recently, we’ve gone the total opposite direction with folks wanting to use a long rod like the 12’ tenkara mentioned earlier, or an 11’ fly rod popular with what people like to call “Euro-nymphing,”

I am regularly asked by guide clients which rod they should bring for a particular stream, the 7’ 3-weight or the 11’ 2-weight. Most of the time, the answer is “either.” Which one do you enjoy fishing with? Because most of the time, neither one is ideal. They’re both specialty rods in my book. The 7’ rod will give you a decided advantage on very small streams and in tighter areas of a bigger stream, but the lack of reach will put you at a significant disadvantage in open pocket water. The 11’ rod puts you at a distinct advantage in larger rivers or open pocket water areas of smaller streams, but it will be a major hindrance in tight spots.

And that’s fine. Which one do you enjoy fishing with? The short rod? Just know that you’ll be sacrificing reach and make it work. The long rod? Just skip past the tight stuff. But if you’re looking for versatility on streams that vary in characteristics, you may want to shift more toward the middle.

I said it 20 years ago and I still say it today. The perfect fly rod for fishing someplace like the Smoky Mountains is a 4-weight in a length between 8’ – 8 ½.’ Is it the absolute perfect rod for every situation? Of course not. But it’s the most versatile. It’s long enough to provide adequate reach when using high-sticking techniques in open water and it’s short enough to be able to maneuver in all but the tightest of streams. If I could only have one rod for the mountains, that’s what it would be.

Hopefully, if you don’t already, you will one day have the desire, passion and means to possess more than one rod for mountain fishing. But even then, I think you’re really pigeon-holing yourself by only getting rods at either extreme. I would start in the middle, with something like an 8 ½’ 4-weight, and add specialty rods from there.

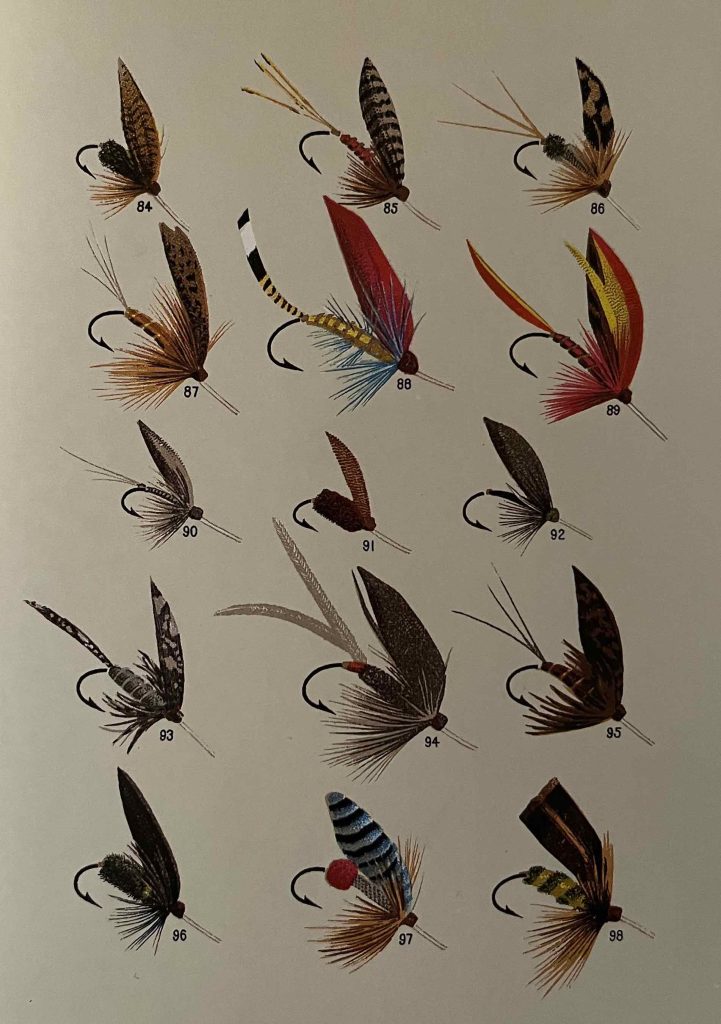

As fly fishermen, we often love to jump on every latest trend, usually in an attempt to improve or simplify. However, in these perpetual attempts to improve and simply, we often end up over complicating things. Because most of the time, the best fly to imitate that nymph is a Pheasant Tail, and the best rod to fish that stream is an 8 ½’ 4-weight.