I could write thousands of tortured words on how to nymph fish. There are countless methods and variables. And they can be determined by anything from water conditions to the type of nymph you’re trying to imitate. Needless to say, it’s a little more than we can chew in a newsletter article. But consider this an introduction to what I like to call active nymphing.

I differentiate it with the word “active” because mostly, we are taught to fish our nymph(s) on a dead drift. In other words, we try to get our nymph to drift at the same speed as the current. This is usually with strike indicator, with no motion or “action” at all. In many situations, this is a highly effective method for catching trout and one that definitely shouldn’t be abandoned. But there are some situations when putting a little movement in the fly, “little” being the key word, may produce a few more fish.

If you’ve spent much time fishing nymphs, this has probably happened to you at some point. You dead-drift your nymph(s) under a strike indicator multiple times through a great run with no results. When you quit paying attention to do something else (probably change flies), the line and nymph(s) straightens downstream, dragging in the current, and a fish hits it.

Nymphs will sometimes deliberately “drift” to other parts of the stream in a sort of migration. Other times, nymphs may unintentionally become dislodged from a rock and find themselves drifting down the stream. In either case, they are most often not particularly good swimmers, and are basically at the mercy of the current. Your dead-drift nymphing technique replicates common scenarios like this. However, some nymphs, like the Isonychias mentioned in the other article in this newsletter, ARE good swimmers. They don’t drift helplessly with the current. Caddis especially tend to be good swimmers.

And at certain times, such as when it’s time to hatch, even poor swimming nymphs will uses gases to “propel” themselves through the water column to reach the surface. These nymphs are often referred to as emergers. During these times, that upward, emerging motion of the nymph is often what triggers the fish to strike. So, that fish you caught “by accident” when you let your line get tight and drag behind you may not have been such a fluke. When your drift ended and the line straightened, your nymph “swung” from the stream bottom to the surface, likely resembling an emerging nymph. The trick now, is to replicate that how and when you want to, rather than by accident when you’re not paying attention.

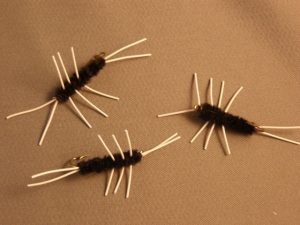

The best way to start with this technique is to find a good stretch of pocket water. Or a nice riffle with some deeper seams and cuts will do. With faster current, you’ll be able to get closer to the fish and employ a high-sticking method. Use a longer rod, probably 8-9’, and use a leader approximately the same length as the rod. Tie on a generic, all-purpose soft-hackle pattern, like a soft-hackle Pheasant Tail or Hares Ear, and put a small split shot about 8” above it. Forget the strike indicator.

In a smaller pocket, keep just a couple of feet of fly line out past the rod tip, and make a short cast up and across to the top of the pocket. You should be slightly more than a rod length away from your target, preferably with a faster current between you and the target (this will help to conceal you from the fish). Keep your rod tip up and out by extending your arm, and try to maintain an approximately 90-degree angle between the line and rod. By keeping your rod tip up, you can keep most of the leader off the water. If you want the nymph to go a little deeper, drop your rod a little lower. It depends on the depth of the water.

Move the rod with the drift at the pace of the current to maintain the 90-degree angle, and allow the drift to continue in front of and slightly below you. You may get a strike during this portion of the drift. If so, you’ll probably feel it since you have most of the slack out of your line, but keep a close eye on your leader. It will tighten if a fish strikes and be another cue for you to set the hook. When you reach the end of the drift (bottom of the pocket), quit moving the rod with the drift. This will force the fly to swing from the bottom to the surface. If the fish hits during this portion of the drift, you will likely feel a very hard tug.

The same method can be used when fishing a bigger pocket or a longer seam in a riffle. You may just be using slightly more line and have a little longer drift. You may also choose to try one more technique on these longer drifts. Start by doing everything as described above. When the fly and line are passing in front of you, give your wrist 3 or 4 intermittent, slight upward twitches. This will allow the fly to “jump” or “pulse” in the current. Keep in mind that you want those wrist twitches to be very slight. Quickly and aggressively “pulling” the fly from the bottom to top will not look natural.

I suggested using a soft-hackle fly for this technique, mainly because the design of the fly lends itself well to the motion-based presentation. But I fish a variety of nymphs in this fashion. Definitely give it a try with your favorite caddis nymphs and emergers. And try it next time that water is a little high and stained from rain. Use a dark Wooly Bugger or a dark, rubber-legged nymph like a Girdle Bug. What you find may surprise you!

More visible leaders with colored butt and mid sections can make this method of fishing much easier. They help a little with strike detection but mostly, they help you see and track the leader and better gauge the depth of the fly. I make leaders specifically for these short-line techniques and they are available for purchase here.

It’s the time of year when certain folks seem to be whispering more at the fly shop. They huddle in corners and peek over their shoulders before saying too much. They’re talking about brown trout. Big ones. Somebody mentioned seeing a decent one around Metcalf Bottoms – about 18-inches. A younger guy innocently asked, “Since when did we start referring to 18-inch browns as just ‘decent’?” The older guy replied with a grin, “October.”

It’s the time of year when certain folks seem to be whispering more at the fly shop. They huddle in corners and peek over their shoulders before saying too much. They’re talking about brown trout. Big ones. Somebody mentioned seeing a decent one around Metcalf Bottoms – about 18-inches. A younger guy innocently asked, “Since when did we start referring to 18-inch browns as just ‘decent’?” The older guy replied with a grin, “October.”

The best prevention for all of these, of course, is good old-fashion bug spray. Bug sprays with higher concentrations of Deet seem to be most effective, but be careful when using them. Deet has the ability to melt plastic. Getting a healthy dose of Deet heavy bug spray on your fingers can wreck a fly line. Just avoid spraying it on your palms and finger tips. If you’re one who likes to spray your hands and rub it on your face, just spray the back of your hands and rub it in that way.

The best prevention for all of these, of course, is good old-fashion bug spray. Bug sprays with higher concentrations of Deet seem to be most effective, but be careful when using them. Deet has the ability to melt plastic. Getting a healthy dose of Deet heavy bug spray on your fingers can wreck a fly line. Just avoid spraying it on your palms and finger tips. If you’re one who likes to spray your hands and rub it on your face, just spray the back of your hands and rub it in that way. the woods, there’s a chance of picking up a tick. Deet based bug sprays will help with that, too. I still try to check myself periodically, particularly at the end of the day. If you do find one on you, there’s an easy way to remove it. Squeeze a dab of medicated lip balm (the gel type that comes in the squeeze tube) onto your finger and smear it on the tick. It will immediately release itself from your skin. Cool, huh?!? I always keep a tube of Carmex in my first aid kit for this reason.

the woods, there’s a chance of picking up a tick. Deet based bug sprays will help with that, too. I still try to check myself periodically, particularly at the end of the day. If you do find one on you, there’s an easy way to remove it. Squeeze a dab of medicated lip balm (the gel type that comes in the squeeze tube) onto your finger and smear it on the tick. It will immediately release itself from your skin. Cool, huh?!? I always keep a tube of Carmex in my first aid kit for this reason. Last month, I talked about ways to simplify your fly selection and offered tips on how to choose flies based on season and what was hatching. Based on the number of questions I had, however, I left out an important part of the process. Many folks said they are often uncertain when to fish a dry fly vs. a nymph.

Last month, I talked about ways to simplify your fly selection and offered tips on how to choose flies based on season and what was hatching. Based on the number of questions I had, however, I left out an important part of the process. Many folks said they are often uncertain when to fish a dry fly vs. a nymph.