There are few things more exciting than watching a bass follow and explode on a well presented popping bug! Check out this video from the folks at The New Fly Fisher for some great tips on how to fish them.

Follow the Leader

For beginners, the leader and tippet represent one of the most misunderstood, or unrealized, components of critical fly fishing gear. Many don’t understand the relationship between the tippet and leader or tippet and fly, while others simply don’t understand what the difference is between the leader and tippet. And while intermediate anglers may have a working knowledge of how the tippet relates to the fly, few take the time to contemplate how the right overall leader design can contribute to their success on the water.

To better understand leader design, let’s start from the beginning and define what the leader is. In simple terms, the leader is the monofilament connection between the heavier plastic fly line and the fly. While it varies in length, the leader typically measures between 7 1/2′ and 9’ and has two primary purposes: To allow for a less visible connection from fly to line and to transfer energy during the fly cast. It tapers from a thick butt section that attaches to the fly line, down to a very fine section that attaches to the fly. The finest section that attaches to the fly is referred to as the tippet.

So, the tippet is the piece attached to the fly and its appropriate size is determined by what size fly you’re fishing and how you’re fishing that fly. At least those are the primary reasons. Other factors such as water level, water speed, and clarity can also contribute to that decision. Smaller tippet sizes are not only less visible to the fish, they offer less resistance in the water, allowing for such benefits as less drag and/or faster sink rates. Of course, smaller tippets are not as strong, but when dead-drifting dry flies or nymphs, the fish is typically “sipping” the passing fly, not ambushing it, so it is not often an aggressive strike that will snap the line. Rather, you are lifting the rod and tightening the line somewhat smoothly, and then all of the shock absorbing properties of your rod come into play to, when used properly, help protect that fine tippet and keep it from breaking.

However, when fishing a streamer fly, you are usually stripping the fly to suggest the movement of a wounded or fleeing baitfish, crayfish, etc. This will most often provoke a more violent strike from the fish, and too light a tippet will often snap under such a jolt. Since you are imparting movement on these flies anyway and a dead drift is not desired, a heavier tippet will better move the fly and better withstand the more aggressive strike.

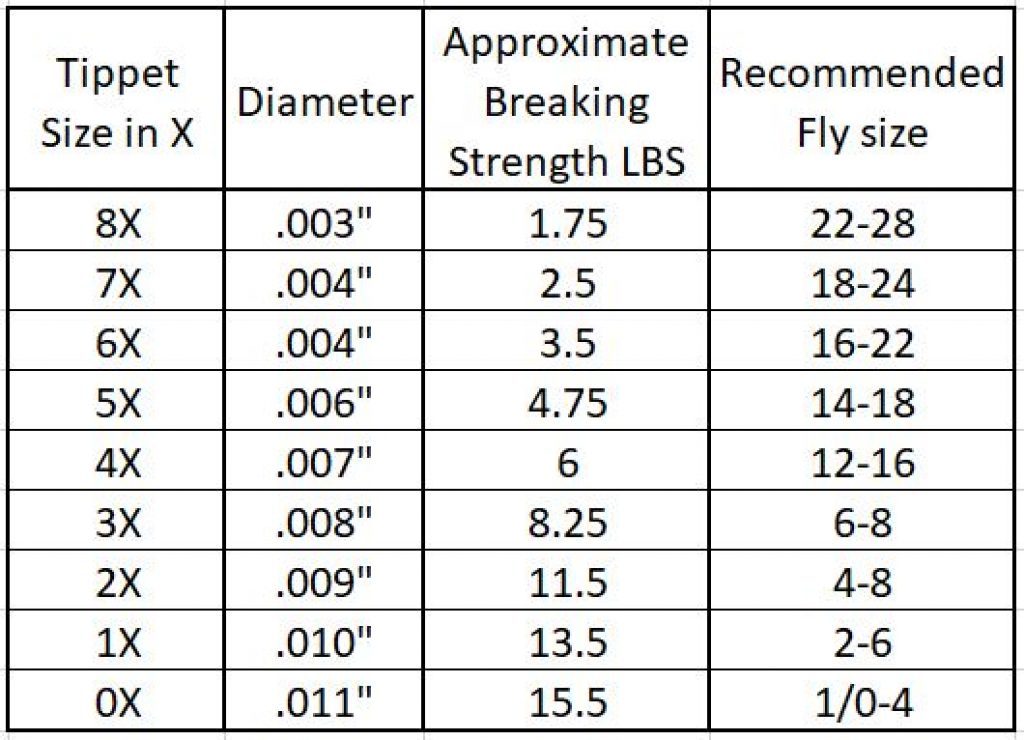

In essence, you want the tippet to balance with the fly for a more efficient cast and drift. For this reason, tippets are sized primarily by their diameter, but also have pound test ratings like spin fishermen may be more accustomed. Those details are all given in the fine print on a tippet spool or leader package but the most obvious marking is a single number followed by an “x” – 4x, 1x, 6x, etc.

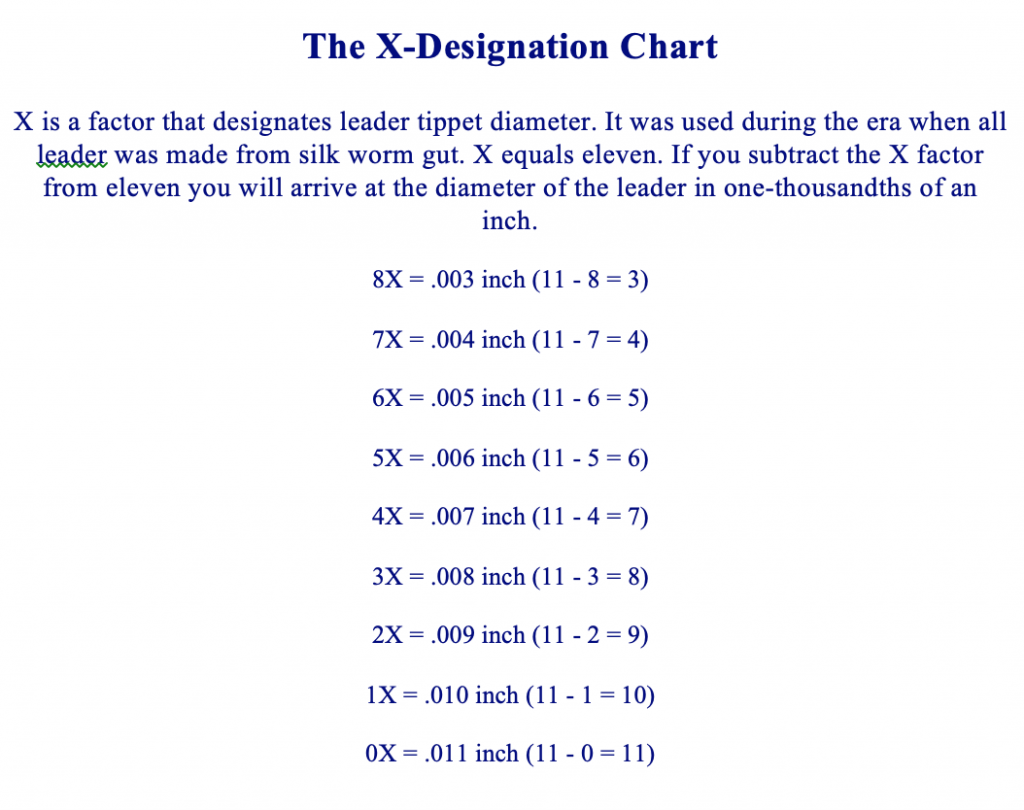

It’s a strange system that can be confusing at first, but it relates directly to the diameter of the tippet, so 6x does not mean 6 pound test. Rather it all corresponds to the base measurement of 0x tippet, which is .011”. If I subtract the diameter of my tippet from this base of .011” I get the appropriate “x” designation and vice versa. In other words, if I have tippet that is .005”, 11 – 5 = 6, or 6x. On the other hand if I subtract the “x” number from .011”, it gives me the actual diameter. For 3x, 11 – 3 = 7, or .007”. I know. Wouldn’t you think there’d be a simpler system?

What you should notice is that the bigger the number, the smaller the tippet. So, 6x is smaller than 3x. Fly (hook) sizes work the same way. A size #18 fly is considerably smaller than a #4 fly. But if you know the size of your fly, there is a pretty simple formula to determine the perfect tippet size to match it. Take the size of the fly and divide by 3. As example, for a size #12 fly, the perfect tippet size is a 4x. Who knew there would be so much math in fly fishing?

It doesn’t need to be this scientific, but using this formula will give you a good baseline in determining a tippet size that will balance with your fly size. You can always fudge up and down as needed. Just keep in mind that when using the above formula, the more you stray to the small side of ideal, the more difficult it will be to turn the fly over with a cast and there’s a better chance of snapping the fly off. The more you stray to big the big side of ideal, the more visible your tippet will be and the more it will negatively impact natural drift.

Without trying to complicate matters too much, the length of the tippet will also impact things like how freely the fly drifts. For example, if you’re trying to dead-drift a size #14 dry fly, you will likely be able to better achieve a drag-free drift with a 5x tippet that is 20” long than with a 6x tippet that is 10” long. Conversely, if you are trying to impart movement on a streamer, a 4x tippet that is 10” long will provide much more control and immediate movement than a 3x tippet that is 20” long.

All of this is a piece to a bigger part which is the leader, and a lot of people don’t understand the difference in the two. Tippet is just a part of what makes up a leader just like tires are part of what makes up a car. If you merely tied 9’ of straight tippet to the fly line, you would certainly be able to execute good drifts but you would have an extremely difficult time casting the fly where you wanted to and would regularly experience the fly and tippet landing in a pile, just inches from the fly line.

Therefore, the leader is tapered and consists of three parts: The butt, the taper, and the tippet. We already know what the tippet does. The thicker butt section turns the leader over with the rest of the cast, which helps eliminate piling. The taper section essentially dampens the energy of the fly cast, allowing the fly and tippet to land softly on the water.

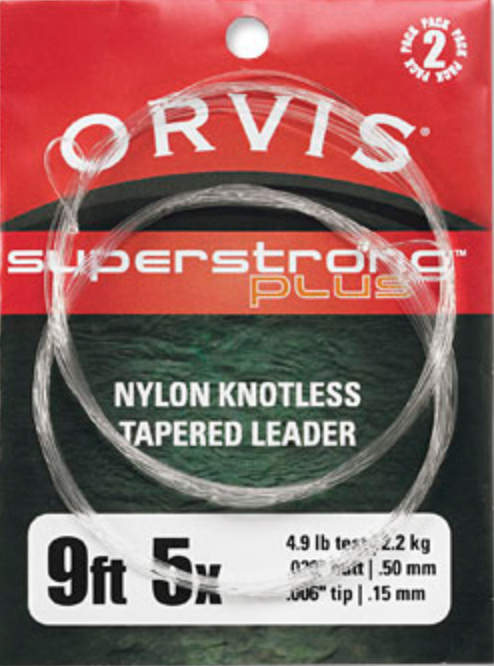

When you buy a tapered leader at a fly shop, it is usually knotless. They achieve the taper by running the nylon material through a machine. On the package, it will indicate the leader’s overall length and its tippet size. So it might indicate that it is a 9’ 5x leader. In fine print, you can also see the exact diameters of the butt and tippet as well as the pound test. It has tippet built in and is ready to go right out of the package. So what’s with the spools of tippet?

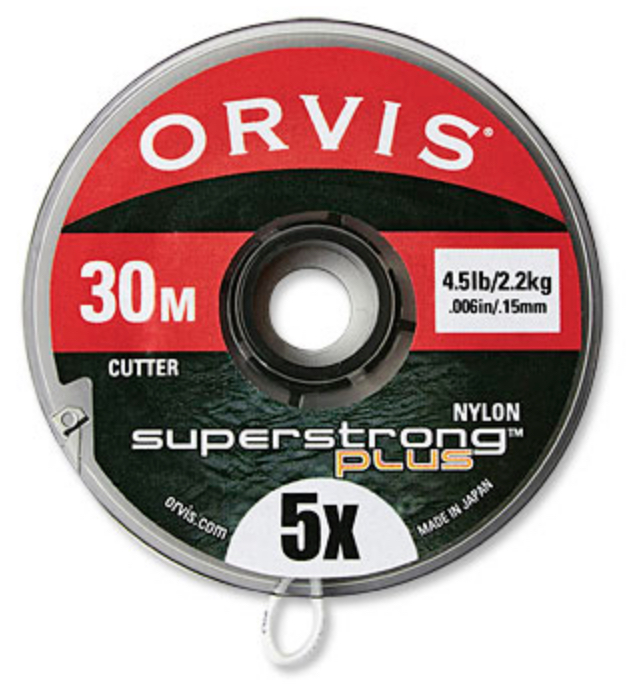

Tippet material can also be purchased on a spool with a number designation as described earlier – 3x, 4x, 5x, etc. This is purely straight tippet with no taper and its primary purpose is to rebuild or alter your leader. When you wear out the tires on your car, you can replace them without having to replace the entire car, and it’s the same with a leader and tippet. Through the course of a day, the tippet on your leader will get gradually shorter as you change flies. Or it may quickly get dramatically shorter if you hang up in a tree or two. What started out as a 9’ 5x leader is no longer 9’ and no longer 5x.

Rather than going to the trouble and expense of changing the entire leader when this happens, you can simply pull an appropriate length of 5x tippet off the spool, tie it to the leader, and you’re back in business. Over time, you’ll cut back so far into the taper that you eventually have to change the leader, but by rebuilding with tippet, you can significantly extend the life of your leader.

As mentioned, you can also use tippet material to alter your leader. You may be using a 9’ 6x leader and want to add an additional few feet of 6x for a better drift, making it a 12’ 6x leader. Or you may be changing flies that vary dramatically in size and style. For example, you might be stripping a #6 Wooly Bugger on a 7 ½’ 3x leader when a hatch of #16 Sulfurs starts to come off. Instead of changing your entire leader, you can simply add a couple of feet of 6x tippet and you have a 9 ½’ 6x leader. Just be sure you’re adding the same size or smaller. Adding a bigger piece to a smaller piece will not only create a weak link above the final section of tippet, it will also create an undesired hinging effect in the leader.

I sometimes tie my leaders rather than buy them from a fly shop. This is done by knotting together different diameters of monofilament to achieve a taper. There are established formulas you can use for this, but through the experience of trial and error, I developed my own formulas that best suit my needs. While I have a lot of specialty leaders, my go-to, everyday trout leaders are all tied ahead of time in a length of 7 ½’ to a tippet size of 3x. Since I’m rarely fishing a tippet size bigger than 3x for trout, this allows me the flexibility to add the final piece of tippet on the stream to match the fly and situation. If I’m going to fish a #14 Parachute Adams, for example, I’ll add a 2’ section of 5x and I’m ready to go.

I first started tying my own leaders when I was on the limited budget of a college student because I realized I could pay $3.50 for a leader or I could make them for about 30 cents each. Over the years, I continued making my own because I prefer them and like being able to design them for my needs. For instance, I find the commercial trout leaders to have too big of a butt section and I don’t like the way they turn over or straighten out. By using a thinner diameter butt and a different type of monofilament for the butt and taper sections, I get a leader that turns over and lays out beautifully. I also like having a few knots throughout the leader as locations to place split shot and strike indicators without them sliding down the line.

I have a variety of other specialized leaders for specific situations. My bass leaders have thicker butt sections to turn over large flies. I have hatch leaders that are long and thin, designed to achieve perfect drifts over wary trout. And I have shorter, small stream leaders for punching flies under tree limbs in extra tight conditions. I also make short leaders designed to fish on sink tip lines when streamer fishing big water.

These are all things to take into consideration when making your own leaders or even when you buy them at the fly shop. Understanding the basics like length and tippet size will inevitably make a difference in your success on the stream. Better understanding how the butt and taper figure into the equation will give you vital tools to begin catching fish that other anglers can’t!

Mending Line

Most of the time when trout fishing with dry flies or nymphs, you try to achieve a drag-free drift. This is also known as a dead drift. Essentially, what this means is you try to make your fly drift at the same speed as the current. That would be simple if the fly was drifting independently down the river. But it’s not. It’s attached to your line. Consequently, line management is a vital skill when it comes to fly fishing success and mending line is a big part of that skill set.

If your leader, or especially your fly line, is in a different current speed than the fly, it will pull or stop the fly when the line tightens. The term we use for this is drag. If your fly is dragging, you won’t catch many trout because it doesn’t look natural. Not only will the trout typically refuse to eat your fly when it has drag, they will often spook. This is especially true when you repeatedly drag a fly over a fish.

When you’re fishing small creeks and/or pocket water, you can often get closer to the fish because the broken currents help conceal you. In those instances, you can usually prevent drag by just keeping most of the line off the water. The less line on the water, the less there is to pull the fly.

But in slower pools or in bigger, deeper water, you may not be able to get as close to the fish. This forces you to make longer casts. As a result, you’ll have more line on the water. The more line you have on the water, the more currents you’ll have pulling it at different speeds.

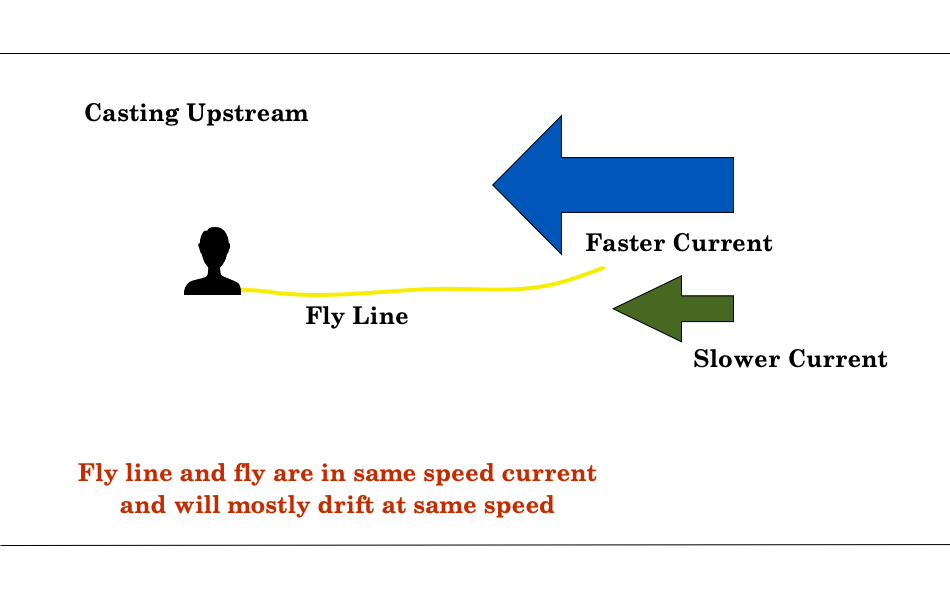

When possible, I like to cast mostly upstream when I’m fishing bigger water. This allows me to stay behind the fish and it puts my fly and line more in the same speed of current. When the fly and line are in the same current speed, line management is much simpler. You mainly just have to strip the slack in as it drift back to you.

However, sometimes a particular run won’t allow for a practical upstream cast. It could be that the depth of the water won’t allow you to get in the proper position. Or maybe it’s a slick with really spooky fish and you’re concerned about casting your line across them. You may decide to get above them and cast downstream.

You have to be careful with this approach because you’re moving into their direct line of sight, and anything you stir up while wading will drift down to them. Excessive debris or a big mud cloud will send them running. The other challenge casting downstream is the drift.

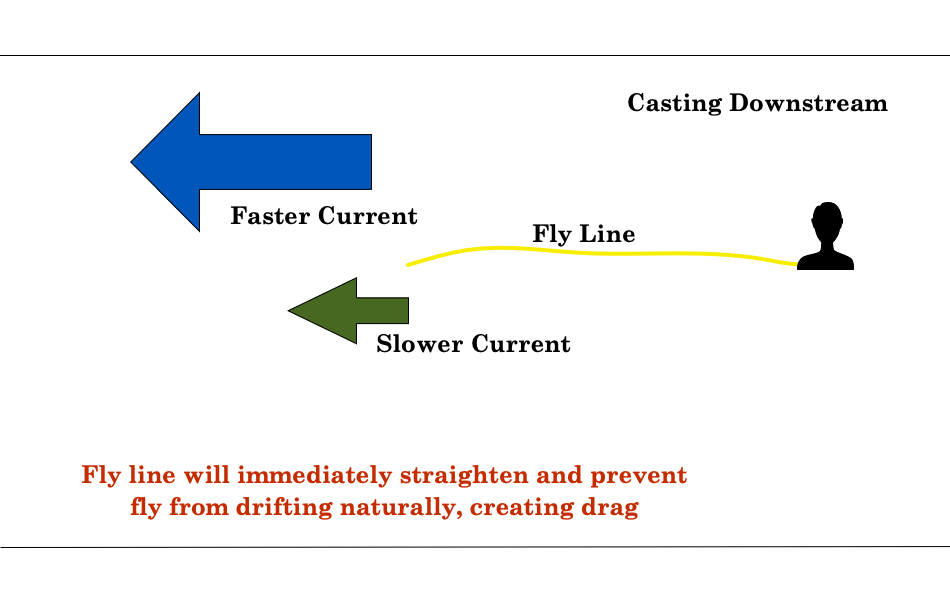

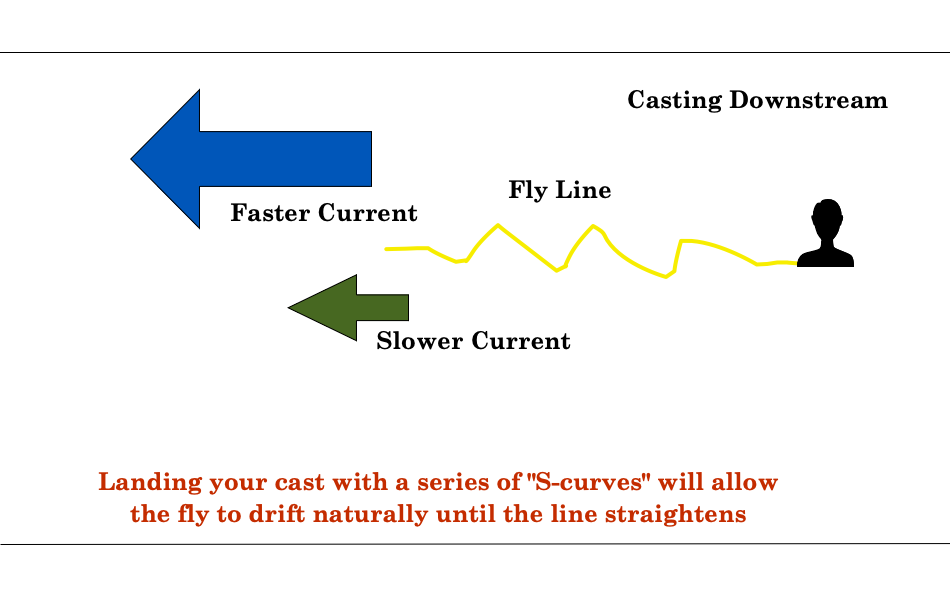

If you make a straight, fully extended cast downstream, your fly will start to drag almost immediately because the tight line will prevent the fly from going anywhere. It just drags in the water. I see a lot of people try to feed line at this point. But if the line is tight from the start, you’re just feeding a dragging fly. The trick is to land your cast with slack in the line. Using something like a pile cast will allow the line to land with little s-curves in it. You’ll be able to achieve a good dead drift while the s-curves straighten out. And if you want it to drift farther, feed line while you have those s-curves to get a nice, long drag-free drift.

The big challenge is when you have to make a longer cast across the river. It’s something I avoid if I can, but often, especially on large rivers, you have no choice. Casting across the river will almost always put your line and fly in different current speeds. And the longer the cast, the more different current speeds your likely to find.

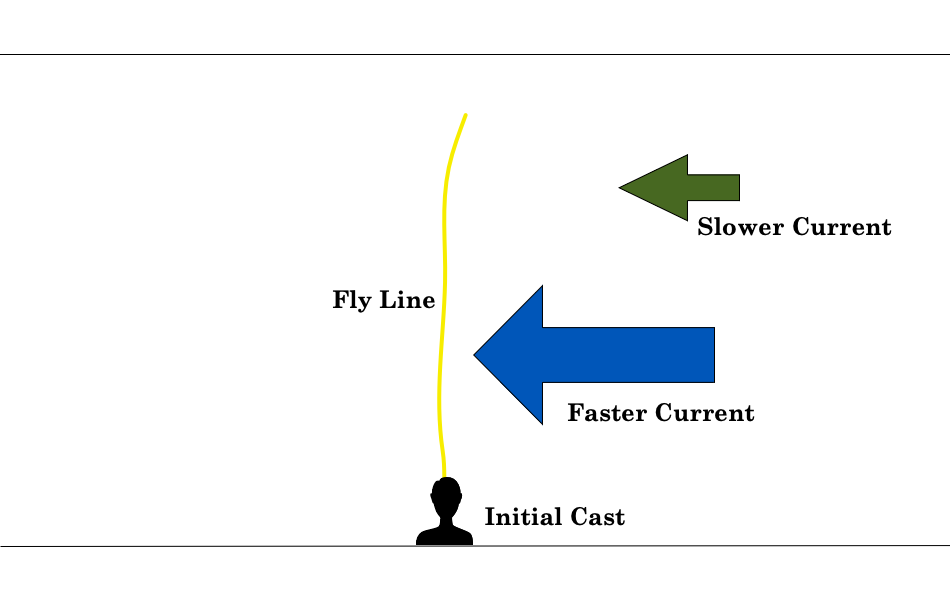

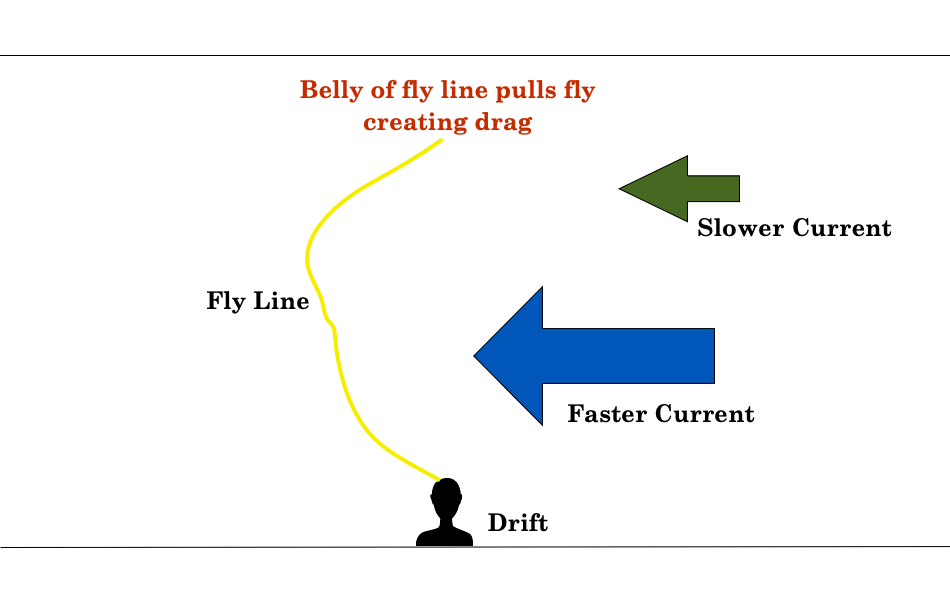

So, let’s say you have a nice, slow current on the other side of a wide run. There’s a fast current between you and the slow current. When you cast your fly into the slow current, your line will lay across the fast the current. Consequently, the fast current pulls the line, the line pulls the fly and you have drag. This is a scenario when you need to mend line.

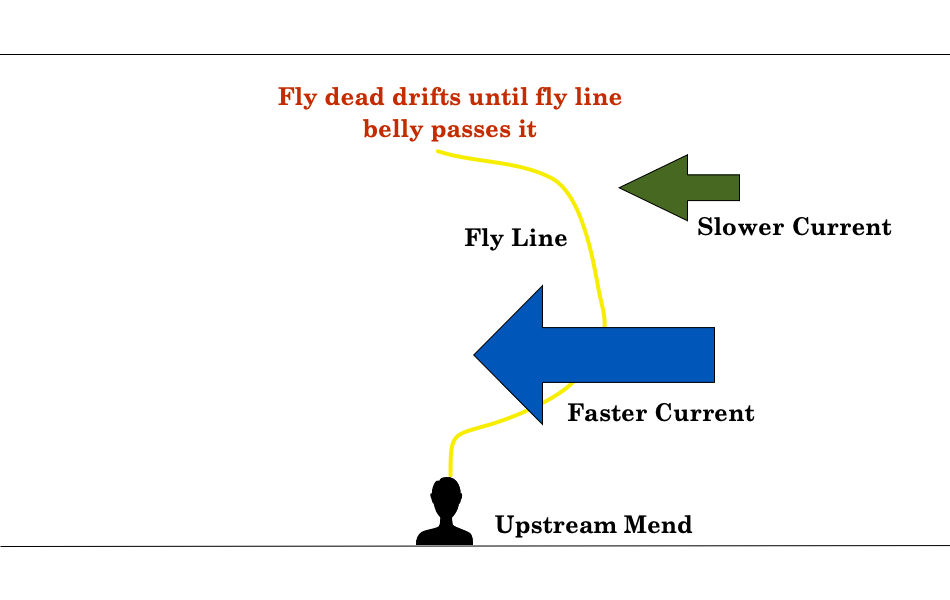

Mending line means that I am going to manipulate the line in such a way that I put it upstream of the fly. By the time the faster current moves the line past the fly, the fly has had an opportunity to naturally drift through the target area. You can make this mend during the cast with what’s called a reach cast. This is known as an aerial mend. Or you can make the mend after the cast has landed by using the rod to flip the belly of the line upstream. Sometimes, longer casts or longer drifts may require you to do both. Longer drifts may also require you to make multiple mends.

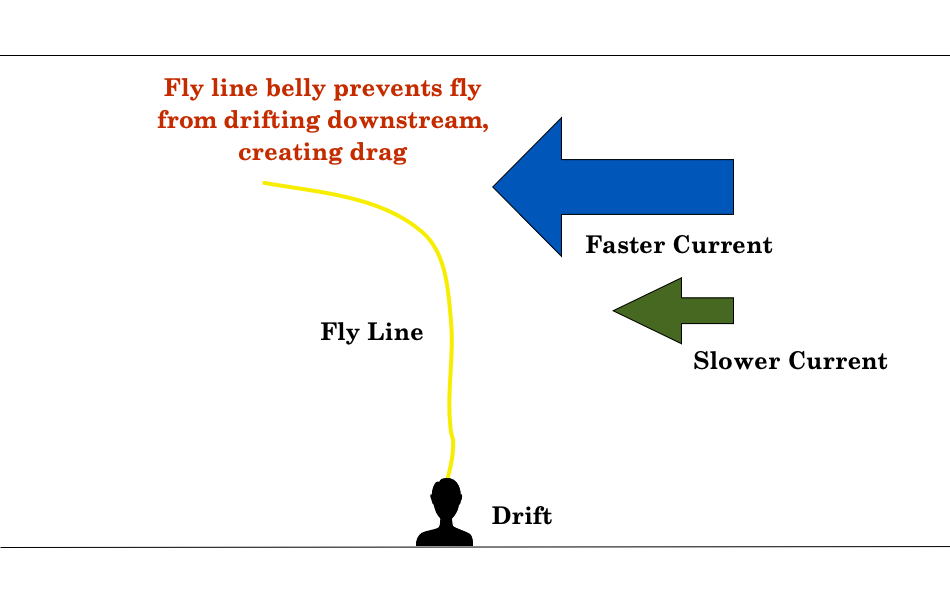

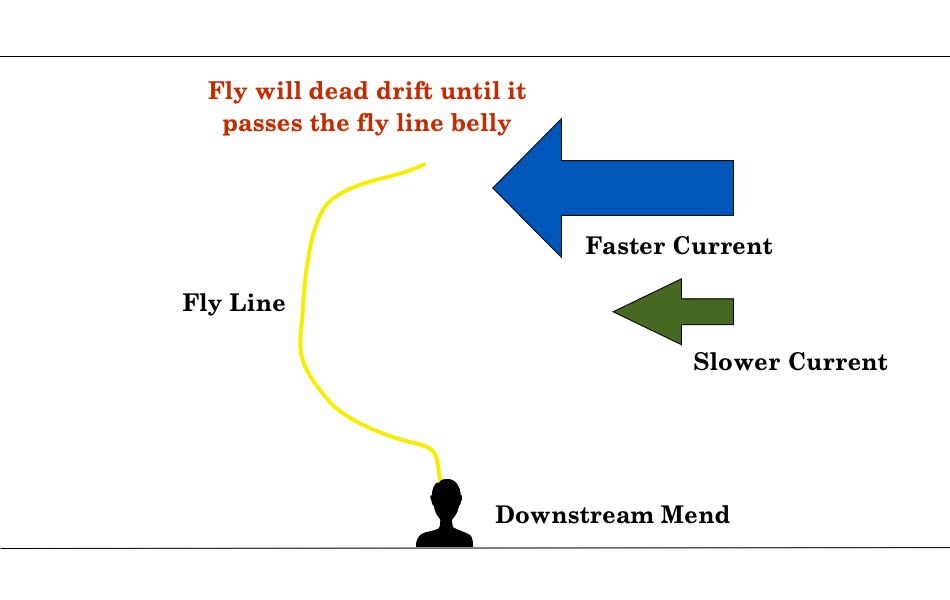

Let’s pose a similar scenario, but this time you’re casting across a slower current and the fly is landing in a faster current. Consequently, the fly will move ahead of the line, tighten and swing (drag) out of the drift lane. In this situation, you want the line downstream of the fly to give the fly time to drift before it overtakes the line. You would use a downstream mend. Like before, this could be achieved with a reach cast and/or by flipping the line downstream after it’s on the water.

Mending is not easy and requires some practice because a lot of it has to do with anticipation and timing. If you wait until the fly starts to drag before you mend, you’ll move the fly out of the drift lane. You need to anticipate that the fly will drag and make your mend before, while you still have slack. This will disrupt the fly’s drift very little, if at all. Again, it will just take some practice.

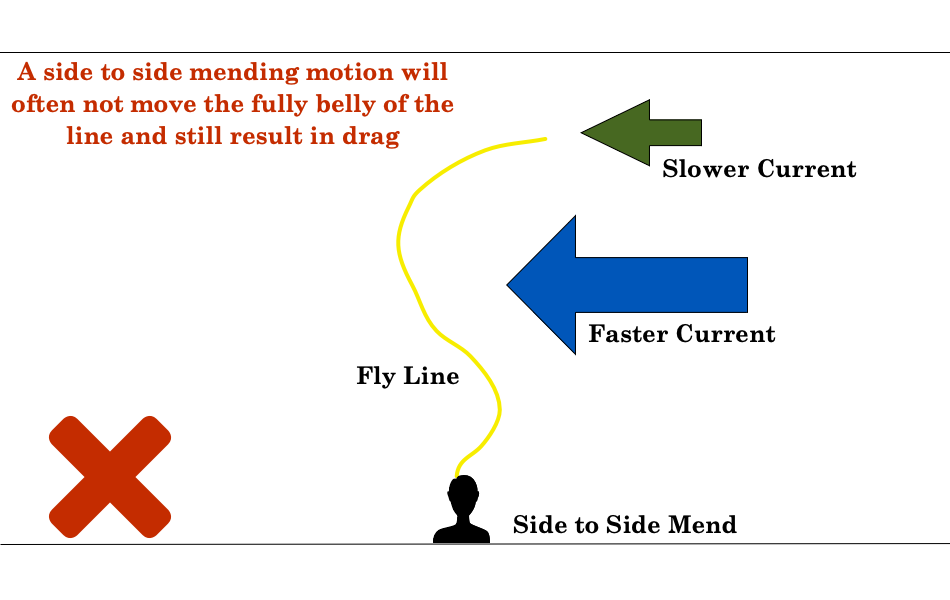

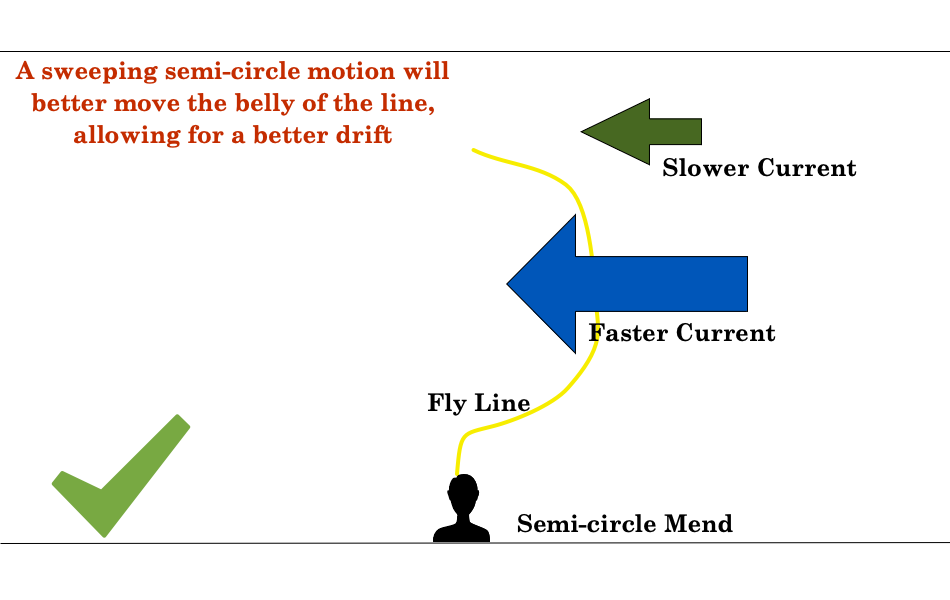

The other big key is how you mend the line. I see a lot of people keep the rod on a level plane and make a side-to-side motion to mend the line. As a result, the line pulls through the water and drags the fly. Instead, point your rod down and toward the line you want to move and make a sweeping, semi-circle motion to move the line. The idea is to essentially pick the line up and place it in a different position… without moving the fly.

How much line you have to move will determine how big of a semi-circle you make. For instance, a big mend with a short line will likely pick the line and the fly up off the water. You don’t want that. A small mend with a long line likely won’t pick up the entire line belly, and you’ll still have drag.

As I mentioned before, it will take some practice. But it is an essential skill when drifting dry flies or nymphs to trout, especially on bigger water. Keep messing with it and before you know it, it will be second nature.

Adjusting Weight When Nymphing

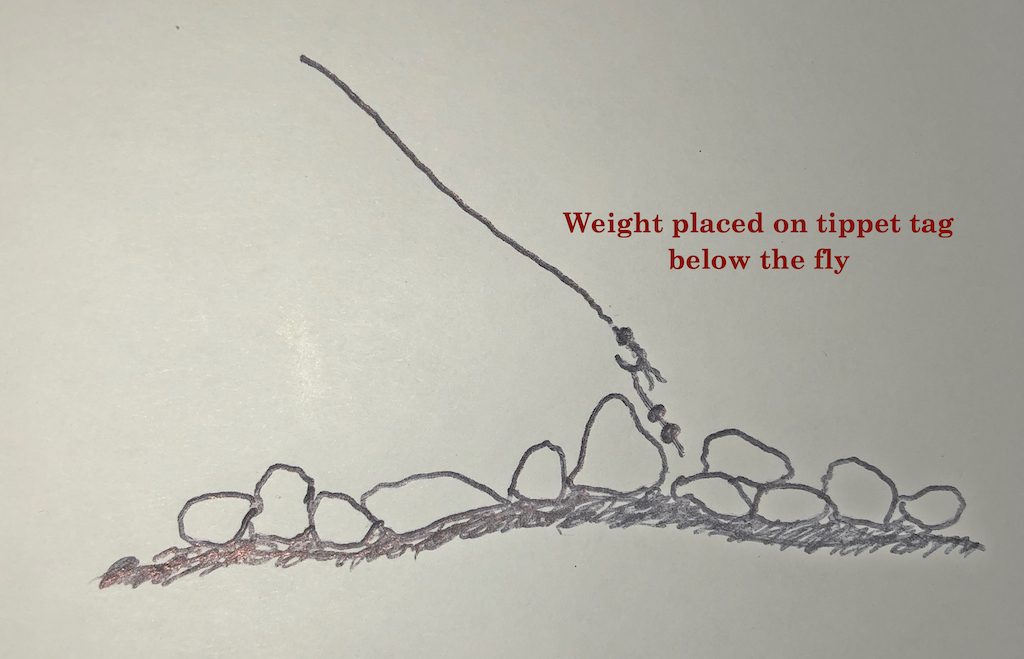

Warning! This article contains terrible illustrations!

Several years ago, I was fishing a stream in the Smokies that I probably know better than any other. It was an early spring day and the water temperature was marginal at around 50-degrees, and the water level was a little high because of recent rainfall. I’d been fishing for two hours and hadn’t even had a strike. I knew it wasn’t a dry fly kind of day. Therefore, I continued to switch nymph patterns, trying to find something that would fool one trout.

Eventually, I decided to stick with one fly pattern, a Pick Pocket, that I had a lot of faith in and to begin altering the way I fished it. Since it was an un-weighted wet fly, I already had one split shot about 8” above it. I began swinging the fly a little more, but the result was the same. Next, I added a second split shot and fished with a mix of swing and dead drift techniques. Nothing. Finally, I added a third split shot and hooked a fish on my second cast. I proceeded to catch another 30 fish or so over the next couple of hours.

I should have known better but we all seem to get too caught up in fly patterns and lose sight of other important factors like drift and depth. Well, I had been fishing good drifts all day, but these fish were hugging the bottom. My fly was not getting, or at least staying, down in their feeding zone.

Do you use split shot when you’re nymphing? There are definitely times when you need to. One of the best nymph fishermen I have ever fished with is Joe Humphreys. It is excruciating to watch him fish because every time he moves to a different spot, he adjusts the amount of weight on his line! But he often catches fish that others don’t because of those adjustments!

Being willing to add or remove split shot to your line is the first step. Knowing where and how to place those weights is the next. For instance, if you put three split shot right next to an already heavily weighted fly, you may have a hard time keeping it off the bottom. So, you have to figure a lot of things, like how heavy your fly is, how deep the water is and how fast the water is. Just the weight of the fly may be all you need to get the nymph near the bottom in slow water, but faster currents may move that fly all over the place. Extra weight can be used not only to get the fly deeper, but also to slow the drift and keep things where they should be.

Shot placement is tricky in places like the Smokies where depth and current speed can vary significantly, even in the same run or pocket. Short casts and good line control can significantly help combat this. Strategic split shot placement can also make a big difference.

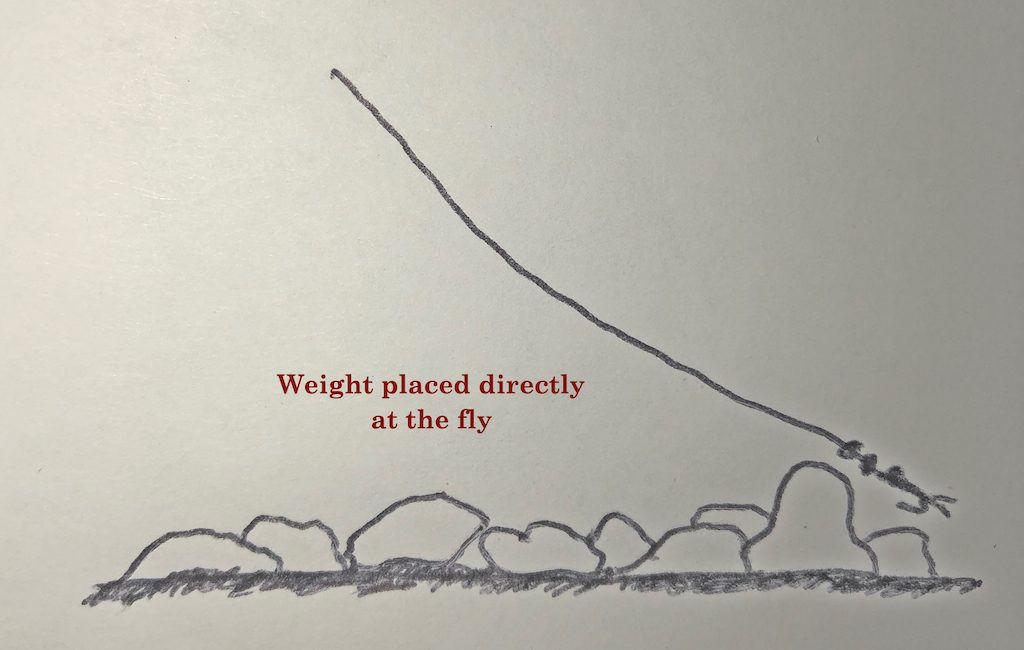

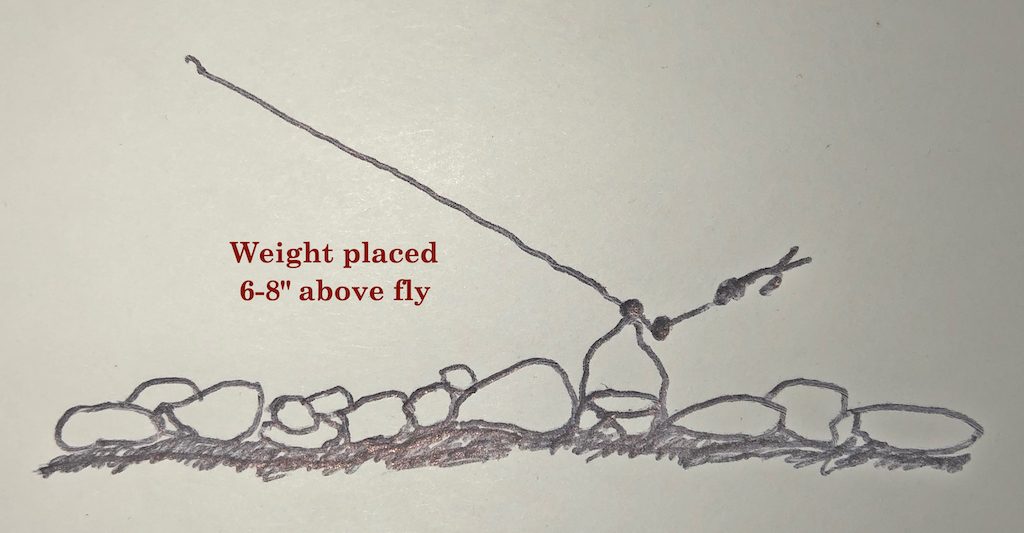

The closer you put the additional weight to the fly, the more you’re going to put the fly on the bottom. As a result, you’ll probably hang up more. But if you put a concentrated amount of weight on a section of leader above the fly, that portion of leader will be what drifts deepest, and the fly will ride above it. The farther the split shot is above the fly, the farther off the bottom the fly will drift.

Of course, there are variables like how heavy the fly is and how much split shot you use. Sometimes you just have to play with it a little bit. When you get as good as Joe Humphreys, you can make those calculations in your head and adjust perfectly for each new spot you fish. Here are a few examples of how you might want to adjust your setup.

The Clinch River often has long, slow slicks that maintain fairly consistent depths. Consequently, the weight of the fly alone should be sufficient to get and keep the fly where I want it. In a 6’ deep plunge pool in the Smokies, I’m going to need a lot of weight to get my fly deep and keep it there because of the water depth and turbulence. I’ll likely use a heavily weighted fly plus a few pieces of split shot placed near the fly. But fishing pocket water in the Smokies, the depth in one pocket probably varies from 12-24”, with a lot of fast currents. Here, I would probably use a lightly weighted (or un-weighted) nymph with one or two split shot placed 6-8” above the fly. This will keep everything down but allow the fly to drift just off the bottom where it won’t hang up as much.

There is another method that some anglers use where a separate piece of tippet is added to the leader or to the back of the fly. The desired number of split shot are then added to that piece of tippet, allowing the fly to remain above the weight. It works, but I find that split shot hanging on a loose, vertical line like that have a greater tendency to get hung up and pulled off on rocks. As with most things, you sometimes have to play with a few methods and figure out what works best for you.

There are, of course, different sizes of split shot and what size you use can certainly determine how many you need to use. I typically use small to medium size shot because it gives me more flexibility and versatility to add or remove as needed.

In any case, if you are only nymphing with a weighted fly under a strike indicator, you are just scratching the surface of nymphing. I encourage you to experiment with different amounts of weight and different weight placements. You’ll probably start catching a few more fish… and maybe a few bigger ones, too!

On the Fly – Unwinding a New Leader

I get to see a lot of things as a fly fishing guide and instructor. Few things make me cringe more than watching someone pull out a new leader and start yanking at either end. The result is inevitably a rat’s nest and nobody wants to start their day that way. It’s an easy thing to avoid and this quick tip will help you get start the day on the right foot!

Spotting Fish

In some fly fishing scenarios, spotting fish is absolutely critical for success. Fishing the saltwater flats for bonefish, redfish, tarpon, etc. or the freshwater mud flats for carp will provide little more than casting practice if you can’t see the fish. In other scenarios, such as fishing a mountain trout stream, you can tell where fish should be by reading the water, and you can catch a lot of fish just by fishing likely spots. But even when fishing trout streams, the ability to spot fish in the water can sometimes allow you to locate and target larger fish. In the fall, this is particularly relevant in the Smokies as large brown trout begin moving into flatter, shallower water preparing to spawn.

Spotting fish can be difficult to learn and there is no substitute for years of experience and practice, but there are a few things that can help you get started. The best place to start is with a pair of polarized sunglasses. The next thing to understand is how trout see, because as you seek out vantage points from which to spot fish, you want to avoid spooking the fish in the process. Here is an article on trout behavior that goes into a little more detail. Now we’re ready to go spot some fish.

Start by looking for fish in slower water. The more broken the surface is, the more difficult it will be to see through it. If possible, try to find a higher vantage point from which to look. This will greatly reduce the amount of light refraction from the water’s surface. Just remember that the higher up you get, the easier it will be for fish to pick up your movement. Avoid standing erect on a large boulder, as your silhouette will be far more pronounced. A high bank with a wooded backdrop is ideal, but you’ll still want to keep your movements slow and minimal. If you are on a large rock above a pool, get on your belly and peek over the edge. Remember the old westerns where the Indians were looking off the rocky bluffs about to attack the wagon train? That’s the idea.

Now that you’re in position, take your time. It’s extremely rare that you’re going to step up to a pool and immediately see a 27” brown trout. You have to methodically scan the pool. Start by reading the water and looking for fish where they should be. Look for obvious feeding areas in and around current lanes and foam lines. Look for areas with obvious cover under and around big rocks and/or fallen trees. They blend in REALLY well, so look long and hard and train your eye to look through the water rather than at it.

It’s hard. You’ll spot plenty of fish that turn out to be rocks or pieces of wood. I once spent 15 minutes casting to a plastic grocery bag hung on an underwater limb. It had the exact shape and movement of a trout! I was in the water and my buddy was above me, watching from a bridge. We were both certain it was a fish!

Movement and shape really are the best giveaways and that’s why it’s so important to take your time and give long looks to those likely spots. You may not see anything at first, then you see a little movement and suddenly the fish is visible. And once you spot one, you often begin to notice others around him. Watching the actual stream bottom, especially on sunnier days, can be helpful too. The movement that you often detect is the shadow of the fish.

Another thing to look for is a flash near the stream bottom. The eyes of a trout are positioned in such a way that they look slightly upward. When feeding on nymphs on the bottom, the trout has to angle his body to see below and will often “twist” his body when he eats the nymph. When this occurs, his white belly reflects light and produces a flash. This is always helpful when looking for fish, but especially in faster water.

All of this is easier the more familiar you are with the stream bottom. If you have a favorite pool, maybe one where you spooked a big fish before, keep going back there and looking. You will inevitably begin memorizing the stream bottom and will more quickly and easily be able to differentiate between rocks and fish. Again, it’s not easy and it takes time but like most things, the more you practice, the better you’ll get.

So, you’re starting to spot some fish… now what? Don’t just jump in and start casting the second you see a nice one. Keep watching. What is the fish doing? If you see a big fish just hugging the bottom, he’s not feeding and you’re wasting your time casting to him. But good news… you found a big fish. You might come back closer to dawn or dusk when he is more likely to be feeding.

If you spot a fish up in the water column, he’s likely feeding. Keep watching him. Is he looking up? Does he consistently feed to his right? Is he staying in one place or is he systematically rotating to different locations within the pool? Pay attention to all of these things and then you can plan your attack. Sometimes with big fish, you’re only going to get one shot and you want to make it count.

How much time you spend looking depends on you. I know guys that do little more than target big brown trout, and they spend far more time watching water than they do fishing. For me, it depends on where I’m fishing and the conditions. If I’m fishing pocket water on a high country brook trout stream, I’m not going to spend much time, if any, looking for big fish. I’m going to cover a lot of water and hit the likely spots. If I’m fishing a big pool on a brown trout river, I’m going to spend at least a few minutes looking before I jump in. If I’m fishing that same big pool in late fall, I’m going to look a lot more thoroughly!

Two Fly Rigs

I almost always fish with two flies when I’m trout fishing. There are just so many advantages to it. Beside the obvious advantage of potentially offering two fly choices to the trout, it provides you the opportunity to simultaneously present a fly in two different feeding columns. Below, I’m going to talk about some of those strategies. And I’ll show a few different ways to rig a dropper system. As a bonus, you get to enjoy some of my horrific artwork!

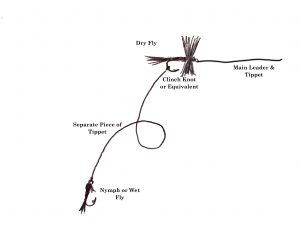

Dry Fly / Dropper

This is the two-fly method with which many fly fishermen are most familiar. It seems that even less experienced fishermen will tell you this is how their guide rigged them up when they were fishing out west during hopper season. When you rig like this, you are typically tying on a larger, or at least more visible, dry fly and attaching a smaller nymph off the back of that dry fly. You’re covering the top of the water with the dry fly and you’re covering usually the middle water column (sometimes the bottom) with the nymph. The dry fly serves as sort of an edible strike indicator for the nymph.

I typically rig this by tying my dry fly directly to the main leader and tippet. I’ll then take probably 18”-24” of tippet material and tie one end to the nymph. The other end attaches to the bend of the hook on the dry fly. There are certainly a lot of variables, such as water depth or where you think the fish might be feeding, that determine how far apart you put the two flies. The amount mentioned above is a pretty good “default setting.” I like to use a clinch knot to connect to the bend of the hook. But whatever knot you usually use to tie a fly on should work fine.

You want to make sure that the flies you select for this set-up compliment each other. They should also be appropriate for the type of water you’re fishing. For example, a small parachute dry fly may not support the weight of a large, heavily weighted nymph. Parachute type patterns will easily support the weight of smaller, lighter nymphs, particularly in slower water. So, a #14 Parachute Adams with a #18 Zebra Midge dropper would be great for a tailwater. And it will work on a slower run or pool in the mountains. But a #14 Parachute Adams with a #8 weighted Tellico nymph, fished in faster water is going to be trouble. Heavily hackled, bushy dry flies or foam dry flies are better choices when fishing in faster water or with heavier nymphs.

With that in mind, know that this method may not be suitable for every situation. For instance, if you need to get a nymph deep, particularly in a faster run, you’re going to need a lot of weight. Using a dry fly–dropper rig is not going to be effective. You’re better off using traditional nymphing techniques for that. But for fishing hatch scenarios where fish are actively feeding on and just below the surface, or for fishing to opportunistic feeders in shallower pocket water, it’s pretty tough to beat.

I also like to fish this same rig with two dry fly flies. On occasion, I’ve found myself in a situation where I have trouble seeing my dry fly. This is usually when trying to imitate something small or dark like a midge, Trico, or BWO. In those situations, I’ll often tie on a larger, more visible dry fly with the smaller, darker dry fly tied about 18” off the back. Sometimes, having the more visible fly as reference allows me to actually see the smaller fly. But if I still can’t see the smaller one, I know to set the hook if I see a rise anywhere within 18” of the visible fly.

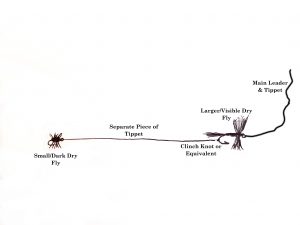

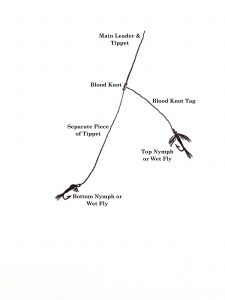

Two Nymphs or Wet Flies

Just like the dry fly-dropper rig above, fishing with two nymphs or wets allows you to cover two different feeding columns. Only now, you’re typically covering the middle column and the bottom. I think another advantage with a two nymph rig is they tend to balance each other out and drift better.

There are a few different ways to rig for this and there are numerous strategies for fly selection and placement. If I have a nymph pattern that the fish are really after, I will sometimes fish two of the exact same fly. There have even been a few occasions when I’ve caught two fish at once! But usually I’m searching and I’m trying to provide the fish with options. I’ll most often have two different fly patterns.

Keep in mind that (most of the time) your lowest fly on the rig will be fished near the bottom while the higher fly will be fished more in the middle column. I try to select and position flies with that in mind. For example, it’s far less likely to find a stonefly in the middle of the water column. They’re going to be found near the stream bottom. So logically, I want my stonefly nymph to be the bottom fly of my two fly rig. On the other hand, an emerging mayfly is more likely to be found in the middle feeding column. So, a soft hackle wet fly would probably be most effective as the top fly on my nymph rig.

You can rig like this with totally different flies or stay in the same “family.” If you’re in the middle of or expecting, say, a caddis hatch, you may rig with a caddis emerger as your top fly and a caddis larva as your bottom fly. I’ve also had a lot of success choosing one nymph to act purely as an attractor. I may tie on a larger or brighter nymph as my top fly and a smaller or subtler nymph as my bottom one. Very often, the brighter or bigger nymph gets their attention, but they eat the subtler nymph below it. I tend to fish the nymphs a little closer together in these situations.

You can rig a pair of nymphs the same way we mentioned above. Tie one directly off the hook bend of the other. This is referred to as the in-line method. This is probably the easiest way to rig and fish two nymphs. But some don’t like this method because they don’t think it allows the top fly to drift freely.

A common way to rig two nymphs that will allow the top fly to drift more freely, is to use a blood knot to attach a section of tippet to the end of your leader. When tying the knot, take care to leave one long tag end, to which you will tie the top fly. The bottom fly will be attached to the end of the new tippet section. This definitely allows the top fly to have more movement and it puts you in more direct contact with both nymphs. Though for me, this method results in a lot more tangles so I only use it for specific scenarios.

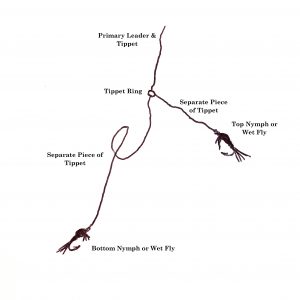

You can also rig quite similarly using a tippet ring (discussed in another article in this newsletter). With a tippet ring attached to the end of your leader, you tie one shorter piece of tippet to the ring, to which you will tie your top fly. And you tie a separate, longer piece of tippet to the ring, to which you’ll tie your bottom fly. This is a pretty simple way to do things but will also likely result in a few more tangles than the in-line method.

These are just examples of a few of the more common methods for fishing and rigging multiple flies. Play around with it and find what combos and techniques work best for you. Never be afraid to experiment!

Matching the Hatch

Probably 25 years ago, I was fishing the Clinch River with a buddy during the sulfur hatch. I won’t get into what has happened to that hatch, but back then, it was epic. Sulfurs would come off by the thousands for 4-6 hours a day for about 3 months. We would drive down from Kentucky to fish it and on most trips, we would both steadily catch fish, many topping 20”.

Probably 25 years ago, I was fishing the Clinch River with a buddy during the sulfur hatch. I won’t get into what has happened to that hatch, but back then, it was epic. Sulfurs would come off by the thousands for 4-6 hours a day for about 3 months. We would drive down from Kentucky to fish it and on most trips, we would both steadily catch fish, many topping 20”.

On this particular trip, the bugs were coming off as good as they ever had, the water was boiling with rises, but we were both getting blanked! We were both going through every type of sulfur dry, emerger, and nymph in the box, all with the same result. Frustration got the best of both of us and we headed to the bank for a smoke, a bad habit we both enjoyed back then. While staring at the river and scratching our heads, it hit us both at the same time as we simultaneously exclaimed, “They’re eating caddis!”

Caddisflies tend to emerge quickly and almost explode off the water. When a trout feeds on one, it will frequently chase it to the top to eat it before it gets away. Sometimes the momentum will cause the fish to come completely out of the water, but at the least, results in a very distinct, splashy rise – not like the delicate sipping rise to a mayfly. Once we stepped away from the river and watched, we both noticed it.

We went back to the water and began looking more closely. Sure enough, there were caddis hatching, too. There was probably one caddis hatching for every 100 sulfurs, but for whatever reason, the trout were keyed in on the caddis. It’s what is referred to as a “masking hatch.” We both switched to the appropriate caddis pattern and were immediately into fish!

That’s not the only time something like that has happened, and each occurrence has trained me to always pay attention and sometimes try to look past the obvious. Here are a few things I’ve learned along the way that may help you solve a hatch riddle sometime.

First, we have to address the basics. If you see fish rising and have a pretty good idea what they’re eating but you’re fly is being ignored, check to see that your fly is the same size as the naturals. Also be certain that your tippet is not too large and that you’re getting a good drift. Presentation is most often the culprit when your fly is being ignored. Next, make certain that the color is a close match to the natural. If you’re fishing a bushy pattern, you might try a more subtle pattern like a Comparadun. If that’s not working, try an emerger fished just under the surface or in the film.

Still not catching them? Take a break and watch the water. You may be able to tell something from the rise rings as I described above. If you don’t learn anything from that, try to find a fish that is rising steadily and watch him. He’s probably feeding in rhythm, like every 10 seconds. Watch his spot and try to time his rises. When you have that down pretty close, try to see what he eats. You should be able to tell if it’s the same kind of bug you’re seeing in the air, or at the very least, whether he’s eating something on or just below the surface. It’s almost like detective work. You sometimes have to go through the process of eliminating suspects before you can zero in on your man!

If fish are actively rising but you don’t see any bugs in the air, check the water. Try to position yourself at the bottom of a feeding lane (downstream of where the fish are feeding) and watch the surface of the water (and just beneath) for drifting bugs. Holding a fine mesh net in the current is a great way to collect what’s coming down the channel. If you don’t have one, your eyeballs will do just fine. If you see some insects, capture one and try to match it with a fly pattern.

Hatches are puzzles and that’s one of the things that makes them fun. Sometimes you solve it right away, sometimes it takes awhile. Just remember that while the fly pattern is a big part of the equation, it’s not the only one. As mentioned above, presentation is huge. In addition to your technique, a smaller tippet and/or a longer overall leader may be the solution. Also consider your approach.

I typically like to cast upstream to fish so that I can stay behind them. But they will sometimes shy away from your fly in slow runs if they see your line or leader. I will sometimes try to get above fish in slow runs and cast down to them so they are sure to see the fly first. To do this, you have to land your cast short of them with slack in the line. Continue feeding slack to enable the fly to naturally drift to them. This is a challenging presentation. It’s critical that you carefully position yourself out of the trout’s line of vision.

Again, it’s a puzzle and there’s not one universal solution to every challenge. Pay attention to your technique and everything that you’re doing (or not doing). Most important, pay attention to the fish. They’ll usually tell you what to do!

Learn more about Smoky Mountain hatches and flies in my hatch guide.

Setting the Hook

If you’ve ever spent anytime fishing in the Smokies, you have missed plenty of strikes. And if you’ve ever been fishing with me in the Smokies, you’ve no doubt heard me say that no matter how good you are and how often you fish, you’re going to miss strikes from these fish. I’d say that’s true most anywhere, but in the Smokies, it’s a guarantee. I’ve had the pleasure of fishing for trout all over the United States and I am yet to find trout anywhere that hit and spit a fly quicker than they do in the Smokies! But while nobody is going to hook them all, there are plenty of things you can do to increase the number of fish you hook.

Before we get into those things, let’s first talk about what exactly is going on when a trout hits your fly. I once guided a gentleman who was having an excellent day as far as activity goes. But he was missing A LOT of strikes. I was giving him plenty of tips along the way but midway through the day, I realized we just weren’t on the same page when, after missing another strike, he commented, “I don’t know how trout even survive.”

“What do you mean,” I asked.

He replied, “It seems like it would be hard for them to survive when they miss their food so often.”

I asked more emphatically this time, “What are you talking about?!?”

He said, “As often as they miss the fly, you know they’ve got to be missing the real food, too.”

I exclaimed, “They’re not missing. You are!”

Don’t get me wrong. I have missed plenty of strikes in my years of fly fishing. Like I said, we all do, but it’s always been my fault, not the trout’s! Sure, every now and then a fish will “short strike” the fly or bump it with his nose, but for most anglers, that is very much the exception. Even when that is the case, it’s probably still your fault. If you’re getting short strikes, it’s probably because your fly is too big, or your tippet is too big, or you have drag… Again, all of those things happen to everyone, but blaming the fish will never fix any of them!

So, what actually happens when a fish hits your fly? It depends on the kind of fly you’re fishing. When you are fishing a streamer (a fly that imitates a baitfish or something else that swims), you are usually stripping it and keeping a tight line. Typically, the trout will chase and/or ambush something they think is a wounded or fleeing baitfish. The strike will usually be rather aggressive and because you have a tight line, you will feel the strike. When you’re swinging wet flies or straight-line nymphing, you usually feel the strike as well, but it’s usually more subtle than the often violent strike that comes on a streamer.

But most of the time on a trout stream, most fly fishermen are imitating aquatic insects that are drifting in the water column. Whether adults on the surface or nymphs below the surface, these bugs are drifting helplessly in the current. When trout feed on these natural insects, it’s not necessary or efficient for them to swim around ambushing them. Rather, a trout will position facing a current, where the insects will drift down his feeding lane. All he has to do is maneuver slightly up, down, or to the side to pick them off. When a trout feeds in this manner, he’s more or less just moving in front of the bug and opening his mouth.

But there are a lot of things coming down the current and some of them, like small twigs or leaves, may look like an insect to a trout. When he takes one of these foreign objects by mistake, he immediately spits it back out. It’s what a trout does all day. Real bug = swallow, stream junk that looks like a bug = spit it out. When you drift an artificial fly down the current and the trout hits it, he immediately spits it out because it’s not real. So you have that split second between when he eats it and when he spits it to set the hook.

Wild trout, like in the Smokies, are highly instinctive and tend to make this decision pretty quickly. Stocked trout were raised in hatcheries where they were fed daily. They tend to “trust” food a little more. Consequently, they’ll hold on to a foreign object (like your fly) a little longer before spitting it out. For that reason, fishermen tend to have a better strike to hook-up ratio on stocked trout vs. wild trout.

In either case, you are rarely going to feel the strike in these scenarios. To avoid drag and present the fly naturally, you will have to have some slack in your line and the fish doesn’t have the fly long enough to tighten your line enough for you to feel it. You will need to visually recognize the strike to tell you when to set the hook. With a dry fly, it’s fairly obvious because the fish will have to break the surface to eat your fly. As soon as you see that, set the hook. It is incredibly difficult in most situations to see a fish eat your nymph, so we often use a strike indicator positioned on the leader. When the fish eats the nymph, it will move the indicator, providing your visual cue to set the hook.

Now, with all of this in mind, here are some tips that may help you connect on a few more fish, particularly when dead-drifting dry flies and nymphs.

- Know that you will probably not feel the strike and trust the visual indication of the strike. Even when streamer fishing when you DO normally feel the strike, there are times when the fish hits between strips when the line is slack. You may not feel it but you’ll see the fly line dart forward. Trust what you see!

- Expect a strike every time the fly is on the water and be ready. As silly as it sounds, many strikes are missed because the fisherman just isn’t paying attention. Stay focused on what you’re doing. Pay no attention to the next pool up the river. Don’t stand there with your hand on your hip. Ignore that bird overhead. Be ready!

- Similar to #2, pay attention to your slack. The cast isn’t when your job ends – it’s when it starts. Particularly when fishing upstream, be prepared to immediately begin collecting excess slack as it drifts back to you. Many fishermen think that they’re missing strikes because they’re too slow when, in fact, their reaction time is fine but they have too much slack to pick up to tighten on the fish. Leave just enough slack to achieve a good drift but no more.

- Keep your casts as short as possible. Not only will you be more accurate and probably get more strikes, but you’ll have less line to move when setting the hook. In some situations, like slow pools, we are forced to make long casts, but fish from better, closer positions when possible.

- Move the line. Your hook set should be like making a quick backcast. In other words, if you miss the strike, the line should go in the air behind you like a backcast. If you miss a strike and all of your line is still on the water in front of you, you didn’t move enough line to set the hook.

- Your hook set should be quick but smooth, and when possible, in an upward motion. A snappy or jerky hook set is a good way to break a tippet. A downward hook setting motion has a tendency to pull the fly out of the fish’s mouth, rather than up through the lip.

Setting the hook is also very much a timing thing. The more time you spend on the water, the better your timing will be. You may even find that you sometimes anticipate the strike just before it happens. And you may find that you have to adjust the timing of your hook set on different rivers. For instance, you may need to slow down a little when fishing for stockers. You may have to speed up a little when fishing for wild trout.

In either case, you’re still going to miss some and that’s okay. As far as fishing problems go, missing strikes is a pretty good one. To miss strikes you have to get strikes. And if you’re getting strikes, you’re doing something right!

Flies: The Hidden Terrestrials

We often hear about the importance of fishing terrestrials in the summer months. Out west, the conversation usually focuses on hoppers. Around here, we talk more about beetles, ants, and inchworms. Regardless, there are a number of land-based insects from beetles, ants and hoppers to cicadas, bees and black flies that find their way into the water during the summer months.

Just the other day on a guide trip, a customer caught a brook trout that had a mouth full of small beetles. The fish had obviously been very recently gorging on them. But there wasn’t a single beetle visible on the surface of that pool. We didn’t see ants, inchworms, or any other terrestrial, either. However, if you used a bug seine in that same pool, you would get an entirely different picture.

The fact is these land-based insects are not particularly good swimmers. Most of them, particularly ants, beetles and inchworms, briefly attempt to swim on the surface of the water but soon are caught by currents and swept below the surface. But nearly every fisherman who fishes terrestrials, fishes them on the surface… and for good reason. Nearly every fly shop or fly manufacturer almost exclusively sells topwater terrestrial patterns. And most of these are constructed of foam or some other highly buoyant material to make the fly ride high on the water.

You can certainly catch plenty of trout on these patterns and have a blast doing it. But you are missing out on A LOT of fish. If you are a fly tier, try tying a few ants with a dubbed body and a hen feather rather than foam and hackle from a rooster neck. Tie some beetles without the high-vis sighter on the back. Instead add a few wraps of lead wire. If you don’t tie flies, place a split shot above your favorite terrestrial pattern next time you go fishing.

A great way to fish them in pocket water is with a straight-line nymphing technique. Allow them to swing at the end of the drift. In pools, fish them a few feet under a strike indicator. Or tie on one of those big, buoyant foam hoppers and drop a submerged beetle or ant about 15” off the back. I probably use this method more than any other.

Learn more about Smoky Mountain hatches and flies in my hatch guide.