This should probably go without saying, but the fly rod is the tool used to cast the line when fly fishing. It is also used to manipulate line on the water after the cast, to set the hook on a fish (usually), and to fight the fish after hooking it. It is certainly one of the most important pieces of your equipment and likely the piece of equipment in which you’ll invest the most money. So, what do you need to consider before making this investment? The three most important characteristics of a fly rod are its length, its line weight designation, and its action.

This should probably go without saying, but the fly rod is the tool used to cast the line when fly fishing. It is also used to manipulate line on the water after the cast, to set the hook on a fish (usually), and to fight the fish after hooking it. It is certainly one of the most important pieces of your equipment and likely the piece of equipment in which you’ll invest the most money. So, what do you need to consider before making this investment? The three most important characteristics of a fly rod are its length, its line weight designation, and its action.

Fly Rod Length

While there are specialty sizes on either end, most common fly rods are going to range from 7’ to 10’ in length. Longer rods aid in keeping the line higher off the water. This can be helpful when trying to achieve longer casts or when trying to cast from a lower position, like sitting in a float tube or canoe. Longer rods are also helpful when trying to reach to keep line off of faster currents. If you’re planning to regularly fish from a float tube or canoe, fish open areas like wide rivers or lakes, or fish a lot of pocket water on medium to large mountain streams, you may want to consider a 9’ to 10’ rod.

Shorter rods are most beneficial in small, brushy streams where a longer rod will be hard to maneuver. If you’re planning to spend most of your time on tiny tributaries and backcountry “blue lines,” you may want to consider a rod in the 7’ to 8’ range.

Line Weight

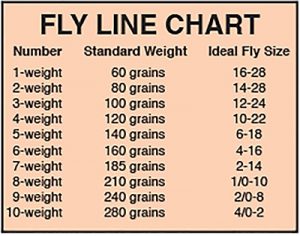

The next thing to consider is the line weight. Each rod has a line weight designation like a 5-weight or a 9-weight. That just indicates what size line it is designed to cast. You typically want to match that to the fly line size. For instance, a 5-weight line will properly load a 5-weight rod and make it cast its best in most situations. Using an 8-weight line on a 5-weight rod would over-load it, resulting in an awkward, “clunky” cast. Using a 3-weight line on a 5-weight rod wouldn’t load it enough. The result is little line control and a significant compromise in accuracy and distance.

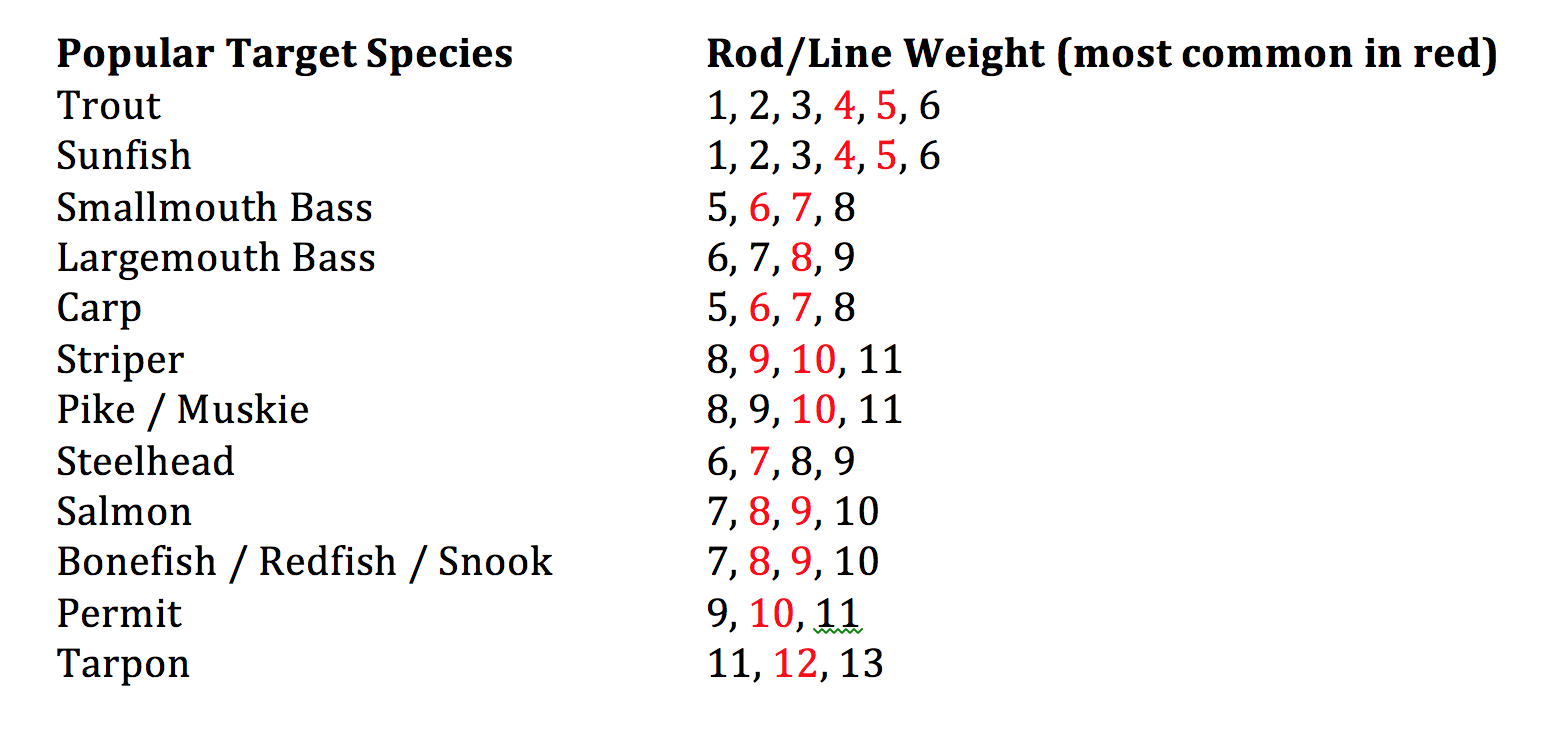

When you’re choosing the line weight of a rod, you want to consider what you will be fishing for. For trout, you are commonly using a 3 to 5-weight. For largemouth bass, you might use a 7 to 9-weight. The difference has little, if anything, to do with the size of the fish. A largemouth won’t snap a 3-weight rod. It’s more about the necessary fly sizes and the required presentations.

For trout, we are most often fishing with smaller flies on a dead drift. Lighter lines allow for a more delicate presentation and create less drag. On the other hand, when fishing for bass, we are often trying to “punch” flies into tight areas and quickly pull fish out of areas with a lot of woody structure. And we are typically using larger, heavier, wind-resistant flies. Often, there is simply not enough weight in a 4-weight line to effectively “turnover” a larger bass bug. Rather than the line carrying the fly on a level plane during the cast, the fly travels below the line, often catching the rod tip or worse, the back of your head!

For trout, we are most often fishing with smaller flies on a dead drift. Lighter lines allow for a more delicate presentation and create less drag. On the other hand, when fishing for bass, we are often trying to “punch” flies into tight areas and quickly pull fish out of areas with a lot of woody structure. And we are typically using larger, heavier, wind-resistant flies. Often, there is simply not enough weight in a 4-weight line to effectively “turnover” a larger bass bug. Rather than the line carrying the fly on a level plane during the cast, the fly travels below the line, often catching the rod tip or worse, the back of your head!

When you get into saltwater species and some large freshwater species like salmon, you may be choosing a particular rod and line weight because of the size of the fish more than the size of the fly. Yes, a 13-weight helps to cast bigger flies to tarpon. But mostly the larger butt section on that size rod is necessary to fight a 150 pound fish!

The other thing that can necessitate a rod with a heavier line weight is wind. Saltwater species like bonefish, snook, redfish, etc. often aren’t particularly big and they don’t demand unusually large flies, but you encounter a lot of wind around the coast. In the American West, you tend to encounter more wind and may consequently want a 6-weight rod for trout. The accompanying chart lists appropriate rod/line weights for common game fish.

Compromise

So, you really need to consider what you’ll be fishing for and where you’ll be fishing to determine the best rod length and weight for your needs. In this part of the country, most people want to fish for bass and bluegill in streams, ponds and lakes, and they want to fish for trout in the mountains and tailwaters. But if you’re just getting into the sport, you probably don’t want to rush out and buy four different fly rod outfits. Fortunately, there is a middle ground.

If you’re the person described in the paragraph above, your ideal rod lengths might range from 7’ to 10’. Your ideal line weights might range from 4 to 7-weight. While it is impossible to get one rod that is perfect for everything, you can sometimes get one rod that is good enough for a lot of things. An 8 ½’ rod is long enough to get by on bigger water and short enough to manage on smaller streams. A 5-weight is light enough for trout fishing and ideal for bluegill. It’s adequate for bass fishing if you scale down your fly size.

Later, if you get really interested in bass fishing, maybe you add a 9’ 8-weight to your arsenal. Or if hiking into small brook trout streams becomes your thing, maybe you add a 7 ½’ 3-weight. You can certainly get by with one rod, but the more diverse your locations and species become, the more necessary it will be to have multiple rod sizes.

Fly Rod Action

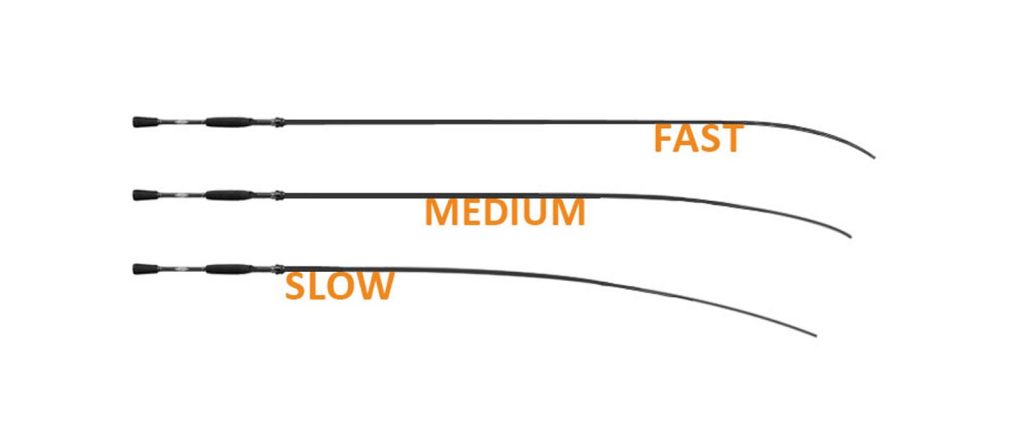

Once you’ve narrowed down the rod size, it’s time to consider the action of the rod. The action of a rod is slow, medium, or fast. A slow action rod feels softer and more “noodly” because it flexes closer to the butt of the rod. A fast action fly rod will feel stiffer because it flexes closer to the tip of the rod. And as you might guess, a medium action rod sort of falls in between, flexing more in the middle of the rod.

Fast action rods are capable of generating more line speed and, in the right hands, more easily achieving greater casting distance. With their stiffer butt sections, they also tend to have more “backbone” when it comes to apply pressure when fighting fish. Most fly rods that are 7-weight or heavier will only be available in a fast action.

Slow action rods are more delicate in their delivery of the line and are more ideal for softer presentations. You tend to feel the fish more on a slow action rod and because it flexes much deeper in the rod, it is capable of better protecting very light tippets. Most rods in the 1 to 3-weight range are slower action rods. Typically, rods in the 4 to 6 weight range are available in a number of different actions.

Your own personal casting style will also be a factor in the best rod action for you. People with a more aggressive casting stroke tend to favor a fast action rod. People with a more relaxed casting stroke tend to favor a slow action rod. Experienced fly casters can pretty easily adjust their casting stroke to the rod. If you’re new to fly fishing, you may not have enough experience to even know your preference. In that case, it’s usually safest to stick to the middle and go with a medium action rod.

Fly Rod Material and Price

In the old days, fly rods were made from bamboo and their price depended on things like who made them and whether or not they were mass-produced. Some of the rods made by certain independent makers are extremely valuable today. Most of the bamboo rods mass-produced by larger companies have little value. Bamboo rods made today are mostly made by independent makers and have price tags in excess of $1000. This is largely because of the amount of time and craftsmanship that goes into making them.

In the old days, fly rods were made from bamboo and their price depended on things like who made them and whether or not they were mass-produced. Some of the rods made by certain independent makers are extremely valuable today. Most of the bamboo rods mass-produced by larger companies have little value. Bamboo rods made today are mostly made by independent makers and have price tags in excess of $1000. This is largely because of the amount of time and craftsmanship that goes into making them.

Today, bamboo rods definitely still have a following much like classic cars have a following. When compared to more “modern” materials, they tend to be a little heavier and almost every bamboo rod will fall into the slow action category. I wouldn’t recommend them to a beginner looking for a rod to get into the sport but for the more seasoned fly fishing enthusiast, they sure are cool!

Fiberglass replaced bamboo in the 50’s as the most common material for fly rods. It was lightweight, and after the trade embargo with China (where rod makers got their bamboo), it was far more available and cheaper to produce. Fiberglass rods have seen a recent return in popularity because of their soft, unique action (slow). Many large rod manufacturers are currently offering select models of fiberglass rods built with more modern components.

Most rods today are made from carbon fiber (graphite) and that has been the case for probably forty years. Carbon fiber is strong and much lighter than fiberglass or bamboo. It can be made in a number of different actions. And it can be made in multiple pieces while still maintaining that action.

Bamboo rods, for instance, had/have metal ferrules (joints). To make a four-piece bamboo rod results not only in a lot of added weight, but “dead spots” at each of those joints. Carbon fiber rods have carbon fiber joints. This is what allows a multi-piece rod to remain light and still maintain its action. Most carbon fiber rods today break down to four sections, allowing for easy storage and travel. Some break down into as many as seven pieces!

The prices of today’s carbon fiber rods are all over the place. Some are mass-produced overseas using less expensive components (guides, reel seat, etc.) and can be found for well under $100. American made rods tend to start around $200. When you bump up to about $400, you’re getting a higher modulus graphite that will feel lighter and crisper. You’ll notice a difference. When you get into the real high-end stuff ($500-$1200), you are getting more technology as well as higher-end components, but most beginner to intermediate fly casters won’t be able to tell the difference.

Keep in mind that many of the things that influence the price of the rod won’t have anything to do with how it casts. For example, a mid to high end rod might have some exotic, $150 piece of wood used for the reel seat. An entry level rod might use a $30 piece of walnut. One might use titanium for the guides while another might use stainless steel.

In other words, if you have the disposable income and want to spend $1200 on a rod, have at it. Just don’t expect it to necessarily cast better or catch more fish! Buy the best rod you can afford. There are some great rods in the $100 – $300 range, many with an unconditional guarantee. That’s right. Some of the major rod manufacturers provide an unconditional guarantee (or variation) on their rods. Orvis, for instance, offers a 25-year guarantee on all but one series of their rods. No matter how it breaks, they’ll fix it or replace it for 25 years! To me, it’s worth spending a little more to get a rod with a good warranty.

Narrow down what size rod you need and what your budget is. After that, it boils down to personal preference. If you decide that an 8 ½’ 5-weight is what you need and you’re willing and able to spend up to $400 on it, go to the fly shop and cast every 8 ½’ 5-weight rod under $400 that they have. Any fly shop worth their salt will have a place for you to cast a rod. And they will gladly let you cast as many as you’d like. And when you do, one of them will just feel right.

We use virtually weightless flies in fly fishing. Many float on the surface of the water. Even weighted flies that sink don’t have enough weight to carry themselves any sort of distance. We use the fly line for that. In essence, the fly line replaces the weight of a lure. When spin fishing, a weighted lure carries a weightless line when cast. In fly fishing, a weighted line carries a weightless lure.

We use virtually weightless flies in fly fishing. Many float on the surface of the water. Even weighted flies that sink don’t have enough weight to carry themselves any sort of distance. We use the fly line for that. In essence, the fly line replaces the weight of a lure. When spin fishing, a weighted lure carries a weightless line when cast. In fly fishing, a weighted line carries a weightless lure.