Warning! This article contains terrible illustrations!

Several years ago, I was fishing a stream in the Smokies that I probably know better than any other. It was an early spring day and the water temperature was marginal at around 50-degrees, and the water level was a little high because of recent rainfall. I’d been fishing for two hours and hadn’t even had a strike. I knew it wasn’t a dry fly kind of day. Therefore, I continued to switch nymph patterns, trying to find something that would fool one trout.

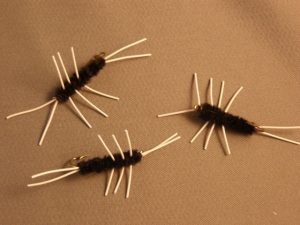

Eventually, I decided to stick with one fly pattern, a Pick Pocket, that I had a lot of faith in and to begin altering the way I fished it. Since it was an un-weighted wet fly, I already had one split shot about 8” above it. I began swinging the fly a little more, but the result was the same. Next, I added a second split shot and fished with a mix of swing and dead drift techniques. Nothing. Finally, I added a third split shot and hooked a fish on my second cast. I proceeded to catch another 30 fish or so over the next couple of hours.

I should have known better but we all seem to get too caught up in fly patterns and lose sight of other important factors like drift and depth. Well, I had been fishing good drifts all day, but these fish were hugging the bottom. My fly was not getting, or at least staying, down in their feeding zone.

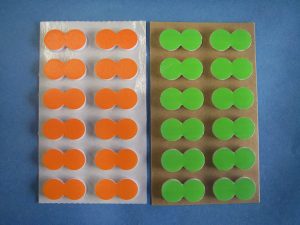

Do you use split shot when you’re nymphing? There are definitely times when you need to. One of the best nymph fishermen I have ever fished with is Joe Humphreys. It is excruciating to watch him fish because every time he moves to a different spot, he adjusts the amount of weight on his line! But he often catches fish that others don’t because of those adjustments!

Being willing to add or remove split shot to your line is the first step. Knowing where and how to place those weights is the next. For instance, if you put three split shot right next to an already heavily weighted fly, you may have a hard time keeping it off the bottom. So, you have to figure a lot of things, like how heavy your fly is, how deep the water is and how fast the water is. Just the weight of the fly may be all you need to get the nymph near the bottom in slow water, but faster currents may move that fly all over the place. Extra weight can be used not only to get the fly deeper, but also to slow the drift and keep things where they should be.

Shot placement is tricky in places like the Smokies where depth and current speed can vary significantly, even in the same run or pocket. Short casts and good line control can significantly help combat this. Strategic split shot placement can also make a big difference.

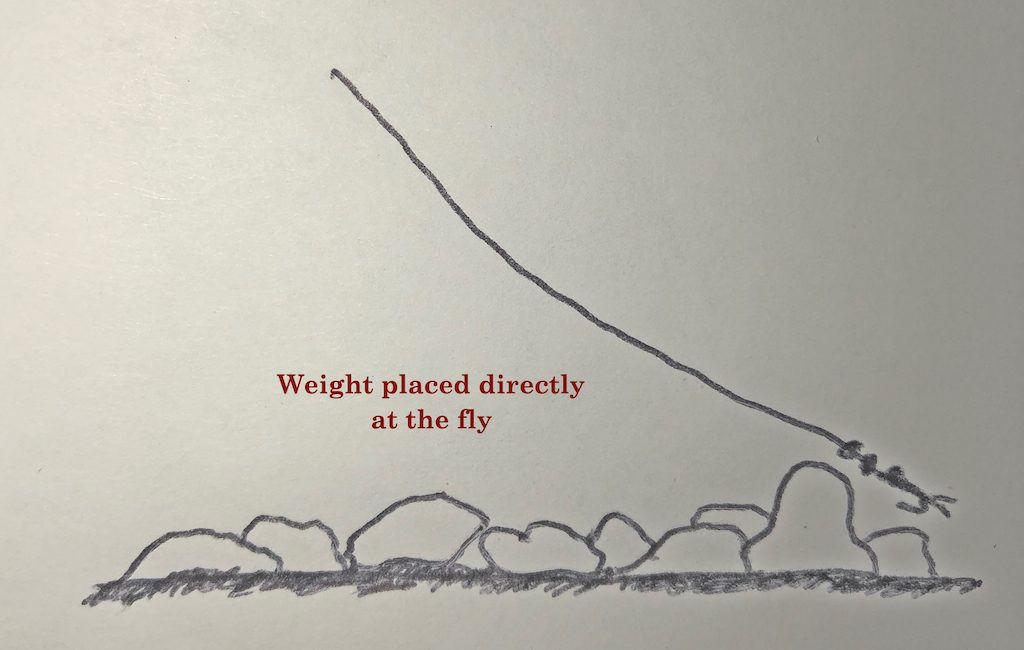

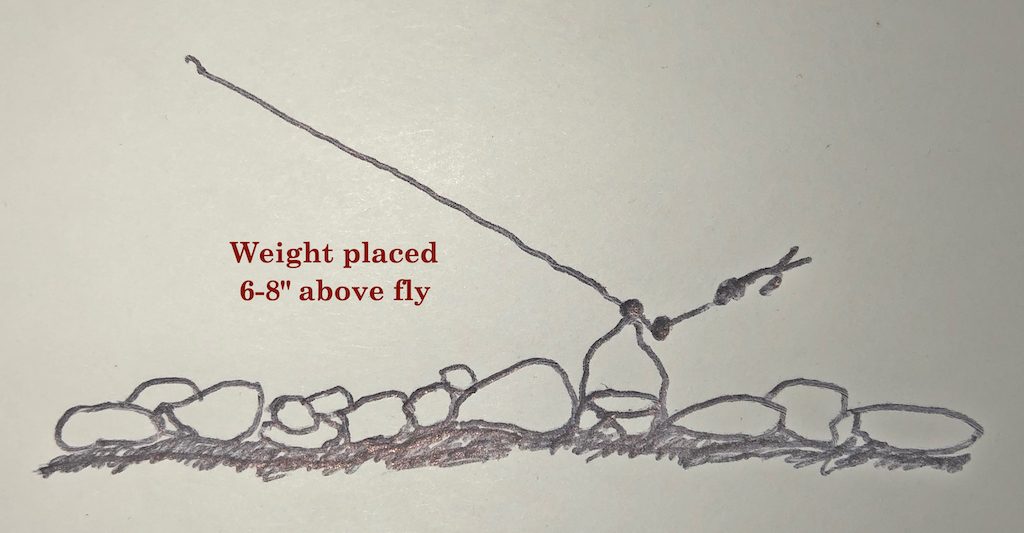

The closer you put the additional weight to the fly, the more you’re going to put the fly on the bottom. As a result, you’ll probably hang up more. But if you put a concentrated amount of weight on a section of leader above the fly, that portion of leader will be what drifts deepest, and the fly will ride above it. The farther the split shot is above the fly, the farther off the bottom the fly will drift.

Of course, there are variables like how heavy the fly is and how much split shot you use. Sometimes you just have to play with it a little bit. When you get as good as Joe Humphreys, you can make those calculations in your head and adjust perfectly for each new spot you fish. Here are a few examples of how you might want to adjust your setup.

The Clinch River often has long, slow slicks that maintain fairly consistent depths. Consequently, the weight of the fly alone should be sufficient to get and keep the fly where I want it. In a 6’ deep plunge pool in the Smokies, I’m going to need a lot of weight to get my fly deep and keep it there because of the water depth and turbulence. I’ll likely use a heavily weighted fly plus a few pieces of split shot placed near the fly. But fishing pocket water in the Smokies, the depth in one pocket probably varies from 12-24”, with a lot of fast currents. Here, I would probably use a lightly weighted (or un-weighted) nymph with one or two split shot placed 6-8” above the fly. This will keep everything down but allow the fly to drift just off the bottom where it won’t hang up as much.

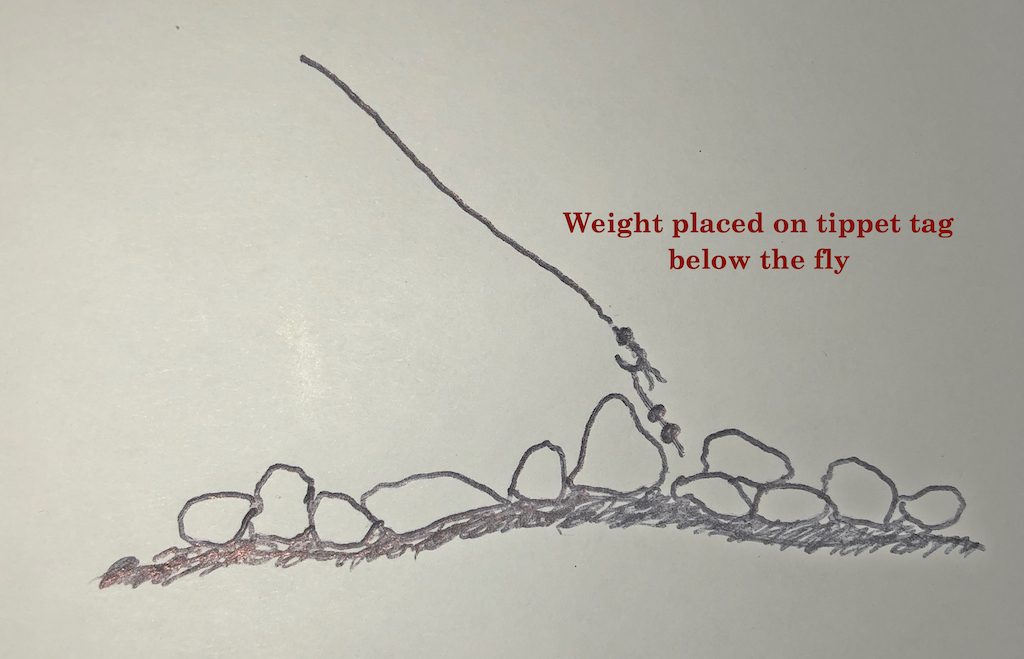

There is another method that some anglers use where a separate piece of tippet is added to the leader or to the back of the fly. The desired number of split shot are then added to that piece of tippet, allowing the fly to remain above the weight. It works, but I find that split shot hanging on a loose, vertical line like that have a greater tendency to get hung up and pulled off on rocks. As with most things, you sometimes have to play with a few methods and figure out what works best for you.

There are, of course, different sizes of split shot and what size you use can certainly determine how many you need to use. I typically use small to medium size shot because it gives me more flexibility and versatility to add or remove as needed.

In any case, if you are only nymphing with a weighted fly under a strike indicator, you are just scratching the surface of nymphing. I encourage you to experiment with different amounts of weight and different weight placements. You’ll probably start catching a few more fish… and maybe a few bigger ones, too!