One of my favorite things to do is fish in very remote places. I love going to places where I’m unlikely to see anyone else and even better, places that few have ever been. But traveling to these places, or anyplace in the backcountry involves a certain amount of risk.

No one ever plans to get lost or to get hurt. And certainly, nobody ever expects that a day of fishing will turn into an overnight stay in the woods. However, no matter who you are, something can always go wrong and when you’re in the backcountry of the mountains, there is a name for people who are not prepared for those unforeseen occurrences when they arise… “Statistics.”

I’ve always been accused of being over prepared and some will probably roll their eyes when they read this article. But things can go bad in a hurry in the wilderness. And if they do, you can hope that someone happens by to help, or you can be prepared to deal with it yourself. And when you travel to some of the remote places I do, the chances of someone happening by are slim. Even when I’m traveling to a location where I’m more likely to see someone, I would much rather be the person prepared to provide aid than to need it.

I always wear a daypack in the backcountry, and I define the backcountry as anyplace I can’t exit and get aid fairly immediately. So, it could be five miles up a trail or it could be a deep roadside gorge that I can’t exit until I get to the other end. In addition to my fishing supplies, I always carry the following items in my backcountry kit and suggest that you do the same.

1) Knife

Whether in the backcountry or not, I was taught as a boy that you never go to the woods without a knife. The needs and uses for a knife in the outdoors are endless.

2) First Aid Kit

From a fall to a sting to a severe cut, you just don’t know when you’re going to hurt yourself. A first aid kit is a must and I’d recommend putting together your own rather than using the pre-made kits. Think about the most likely injuries you could suffer as well as any personal issues you may have, such as bee allergies, and pack your first aid kit with items to treat those things.

3) Whistle

Even when you’re in an area where there are more people, if you should injure yourself in the stream or anywhere else out of sight of the trail, help may not be able to see or hear you. A whistle or other loud sounding device can signal others that you’re in distress. It can also be a tool to scare away aggressive wildlife.

4) Bear Spray

Speaking of aggressive wildlife, I always carry bear spray with me in the backcountry. While it can provide comfort and protection against aggressive bears and other wildlife, it can also be a useful weapon against undesirable people. Anyone remember the machete wielding killer on the Appalachian Trail a few years ago?

5) Topo Map

Certainly this can include GPS devices but a good old fashion paper map won’t run out of batteries. Learn how to read a topo map if you don’t already and keep one with you. I can’t tell you how many lost hikers I’ve encountered and set straight in the backcountry who didn’t have a map.

6) Fire Starting Tools

I always carry waterproof matches, a fire stick and a small amount of dry tinder in my pack. This is in case I, for whatever reason, unexpectedly must spend the night in the woods. Or maybe I take a spill in the water on a cool day and need to prevent hypothermia.

7) Emergency Space Blanket

Much like fire starting tools, this may be used for warmth and/or shelter in case of an unexpected overnight stay or as prevention/treatment for hypothermia.

8) Water Purification

I always carry water with me on a fishing trip or hike. But if it becomes an unexpected extended stay, I want a way to purify water. A LifeStraw is a simple, light, packable option.

9) Paracord

Much like a knife, paracord has multiple uses in the outdoors whether in the backcountry or not. It’s light, small and strong and can be used for simple “emergencies” like replacing a broken boot lace to more serious tasks like constructing a shelter for an unforeseen overnight.

Additional Thoughts

I don’t usually carry a map on guided trips or on many solo trips in the Smokies, only because I am so intimately familiar with those locations. But I take one anytime I go someplace I’ve never been or have only been to a few times. Otherwise, I never travel in the backcountry without the above-mentioned items.

Additionally, although I do it routinely, it’s not a very good idea to fish the backcountry by yourself. Take a buddy and always let someone know where you’re going to be. If you tend to go to really remote spots, you may consider carrying some sort of GPS beacon. They allow you to send an SOS if you get into trouble and some offer text messaging if you need to message a potentially worried loved one when you’re running way late. It didn’t make my list of essentials, but my wife insisted I take one on my “extreme” excursions.

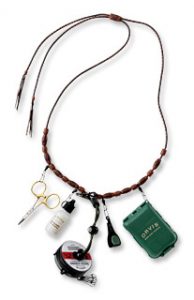

As with most things in fly fishing, fishing packs and vests have come a long way over the years. The great thing about that is you now have a seemingly endless array of ways to carry and organize your on-stream tools and accessories. The bad thing is those seemingly endless choices can be a bit overwhelming.

As with most things in fly fishing, fishing packs and vests have come a long way over the years. The great thing about that is you now have a seemingly endless array of ways to carry and organize your on-stream tools and accessories. The bad thing is those seemingly endless choices can be a bit overwhelming.

I’m a bit of an oddball. This is not exactly breaking news for most folks who know me. But to paraphrase John Gierach, “If, from time to time, people don’t walk away from you shaking their head… You’re doing something wrong.” I could certainly dedicate an entire article, or even a book, to my oddball qualities. But I am referring to one specific oddball quality. I fish and guide with a set-up that combines a pack and fly boxes all in one contraption. You’ve seen it. It’s my chest fly box, custom built by the

I’m a bit of an oddball. This is not exactly breaking news for most folks who know me. But to paraphrase John Gierach, “If, from time to time, people don’t walk away from you shaking their head… You’re doing something wrong.” I could certainly dedicate an entire article, or even a book, to my oddball qualities. But I am referring to one specific oddball quality. I fish and guide with a set-up that combines a pack and fly boxes all in one contraption. You’ve seen it. It’s my chest fly box, custom built by the

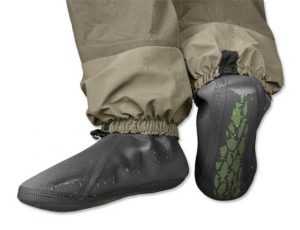

Putting on waders hardly sounds challenging enough to warrant advice. But there are a couple of things you can do that will make you more comfortable during the day. More important, there are things to do to protect and extend the life of your waders.

Putting on waders hardly sounds challenging enough to warrant advice. But there are a couple of things you can do that will make you more comfortable during the day. More important, there are things to do to protect and extend the life of your waders.

When we first met, I cringed as he pulled his rod from the trunk of his car. It was not in a tube and there were a variety of items piled on top of it. I’ve seen a lot of rods break over the years, but I’ve never seen a single one break while it was in the tube. If you knew him, it would come as no surprise that he forgot to bring a reel for the rod, so he ended up using one of mine.

When we first met, I cringed as he pulled his rod from the trunk of his car. It was not in a tube and there were a variety of items piled on top of it. I’ve seen a lot of rods break over the years, but I’ve never seen a single one break while it was in the tube. If you knew him, it would come as no surprise that he forgot to bring a reel for the rod, so he ended up using one of mine.